Looking for the essence of the dumpling, in their most basic form dumplings are cooked dough in the shape of balls, cylinders or pockets.

Uzbek manti |

Tamal from Oaxaca, Mexico |

Czech apricot dumpling |

Fried Chinese wonton |

Italian potato gnocchi |

Czech potato dumplings filled with ground smoked pork |

Apicius, a 2000-year-old Roman cookbook with a recipe for dumplings. |

In this essay, we will leave the more exotic Asian and Meso-American dumpling varieties for another time, and focus instead on Europe. Dishes falling under the definition of dumplings include:

- Ravioli - filled pasta dumplings, composed of a filling sealed between two layers of thin egg pasta dough; most commonly filled with ricotta cheese and spinach and served with tomasto sauce; originating in in the 14th century in Venice and in Tuscany

- Tortellini, Tortelloni and Capeletti - filled pasta dumpling, composed of a filling sealed between two layers of thin egg pasta dough, shaped into a ring; Tortellini and their larger relative the Tortelloni originate from the northern Italian region of Emilia and are traditionally stuffed with a mix of local meats or cheese; Cappelletti originate from teh region of Romagna and are filled only with cheese,

- Gnocchi - small Italian dumplings made from semolina flour, wheat flour, finely-grated potatoes or bread crumbs; dating back to Roman times,

- Zillertaler Krapfen - deep-fried half-circles from Tirol resembling Ravioli, but filled with typical Tyrolean items such as potatoes, mountain cheese, quark, chives, salt and pepper,

- Maultaschen - anotehr Ravioli-like pasta dumpling, but larger; filled with minced smoked meat, spinach, bread crumbs and onions, and flavored with pepper, parsley and nutmeg,

- Spätzle - small lumps of flour and egg dough boiled in water, originating from Austria and southern Germany, bearing an evolutionary resemblance to the Italian Gnocchi,

- Halušky - the same as potato gnocchi in Italy (Gnocchi di patate), but originating from Slovakia,

- Nokedli - the Hungarian equivalent to the Austrian Spätzle,

Bavarian Bread Dumpling |

Czech Bread Dumplings |

- Tyrolean Bread Dumplings (called Canederli in the Italian part of Tyrol) - round, tennis-ball size,

- Tyrolean Lard Dumplings (Tiroler Speckknödel) - round, tennis-ball size,

- Bavarian Potato Dumplings (Bayrische Semmelknödel) - round, tennis-ball size,

- Bavarian Bread Dumplings (Bayrische Kartoffelknödel) - round, tennis-ball size,

- Czech Bread Dumplings (Houskové knedlíky) - slices of a long, salami-thickness cylinder,

- Czech Potato Dumplings (Bramborové knedlíky) - slices of a long, salami-thickness cylinder,

- Czech Raised Dumplings (Kynuté houskové knedlíky) - slices of a long, salami-thickness cylinder,

- Czech Lard Dumplings (Špekové knedlíky) - round, tennis-ball size,

- Karlsbad Dumplings (Karlovarský knedlík) - slices of a long, salami-thickness cylinder,

- Serviettenknödel (called Vídeňský knedlík in the Czech Republic) round, tennis-ball size or a long cylinder, sliced,

- Potato dumplings stuffed with ground pork (Bramborové knedlíky plněné uzeným masem) - round, golf-ball size,

- Czech Chlupaté knedlíky - gnocchi-size lumps,

- Czech Sýrové knedlíky (cheese dumplings) - round, tennis-ball size,

- Játrové knedlíky (Leberknödel) - round, golf- to tennis-ball size, used in beef broth.

Not to be omitted are the Austrian and Czech sweet fruit dumplings:

- Appricot dumplings (Marillenknödel in Austria, Meruňkové knedlíky in the Czech republic) - round, between a golf ball and a tennis ball in size; in Austria, made with with either potato dough, cream puff pastry or curd-cheese dough, served coated in browned bread crumbs, and sprinkled with powdered sugar (Wachauer Marillenknödel); in the Czech Republic mostly made of flour dough (although a potato-dough variety also exists) and topped with melted butter, sugar and grated curd-cheese),

- Strawberry Dumplings (Jahodové knedlíky) - round, between a golf ball and a tennis ball in size; made of flour dough and topped with melted butter, sugar and grated curd-cheese),

- Blueberry Dumplings (Borůvkové knedlíky) - round, between a golf ball and a tennis ball in size; made of flour dough and topped with melted butter, sugar and grated curd-cheese),

- Plum-Stew Dumplings (Powidlknödel, Povidlové knedlíky) - round, between a golf ball and a tennis ball in size; with a filling of Powidl (or povidla), a plum stew from Austria and the Czech Republic; differs from jam or marmalade in that it is prepared without additional sweeteners or gelling agents).

Bavarian bread dumplings. |

Czech bread dumplings. |

Banner U Glaubiců in Prague. |

There appear to be two distinct lineage families within the European dumpling population. The first one is the Italian family, which includes two subgroups: solid small pasta-dumplings such as Gnocchi, Spätzle, Halušky and Nokedli, and filled pasta-dumplings such as Ravioli, Tortellini, Tortelloni, Capeletti, Tyrolean Krapfen, and Schwabian Maultaschen. The second family are the Central European dumplings, big, either round or long and cylindrical, filled or unfilled, consisting of bread dumplings, potato dumplings, and raised dumplings.

The Roman Empire at its greatest extent in 117 AD. |

Reenactment of Legio XV "Apollinaris". |

"The Vitruvian Man" by Leonardo da Vinci. |

Venetian and Genoan trade routes. |

Doge's Palace (Palazzo Ducale) in Venice. |

Frozen dumplings in present-day Kazakh supermarket. |

Italian Ravioli. |

Kyrgyz Samosas. |

Once Ravioli and Tortellini became established in Tuscany and Venice, it is not difficult to imagine their spread throughout Europe. Italy has always been the focal point of fashion. Good food, good music, and good art always comes from Italy. With so many noble families

The Belvedere in Prague, designed by the Italian architect Paolo della Stella, built 1538-1565. |

Kolowrat Palace in Prague, designed and built in 1716 by Jan Blažej Santini, a Czech of Italian descent, and Matthias Bernhard Braun, an Austrian. |

Hofburg Palace in Vienna, designed by Italian arcitects Filiberto Luchese, and Lodovico Burnacini and Martino and Domenico Carlone, Lukas von Hildebrandt (an Austrian of Italian descent), and the Austrian architect Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach. |

Thun-Hohenstein Palace in Prague, designed and built in 1609 by Giovanni Antonio Canevalli, an Italian living in Bohemia, and Jean Baptiste Mathey, a Frenchman. |

So far, so good. This explains the first family of European dumplings: those that in one way or another came from Italy. The other family are the Central European "big dumplings" that originated in Austria, Bavaria, Bohemia and Tyrol. These include the various forms of flour and potato dumplings (the round Speckknödel, Semmelknödel) and Kartoffelknödel, and the sliced Houskové knedlíky, Bramborové knedlíky and Karlovarský knedlík), as well as the Jewish Matzah balls (kneydl, knaidel or kneidel). Not to be forgotten are the sweet dumplings such as Marillenknödel (aprisot dumplings), Jahodové knedlíky (strawberry dumplings) and Powidlknödel (plum-stew dumplings).

In her recent paper, Professor Jennifer Jordan from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee suggested that the origins of bread dumplings lie in Bohemia, the western part of the Czech Republic adjacent to Germany. She suggests that various dumpling histories cite the centrality of Bohemia as a dumpling ground-zero, from which Central European dumpling culture radiated outward. At the same time, Hannes Etzlstorfer writes in the 2006 book "Küchenkunst und Tafelkultur" that the classic dumpling province is Tyrol, with its great variety of bacon, spinach, and cheese that are used as a side dish and eaten in soup. Both are correct, because at the time these dumplings originated, this was all one country.

Dumping fest in Upper Austria. |

The dumplings diversity found in Upper Austria is indeed formidable, giving the state its rightful place among dumpling superpowers. The question remains, however, to what extent is this perceived vast variety a function of scouring every local village for grandma's recipes, promoting it and marketing it? Bohemia, Bavaria and Tyrol also lay claim to be the birthplace of the Central European dumpling. It needs to be kept in mind that Austria, Bohemia (western Czech Republic) and Tyrol were one country for several centuries, first under the Habsburg Monarchy and then under the Austrian Empire. Beyond that, all four of these kingdoms were all once part of something even bigger, namely the Holy Roman Empire. It is therefore little surprise that all of the above share a common cultural heritage, which obviously the fodo culture. Common cultural roots, including culinary traditions, run deep in this region. Although languages differ (Czech and various German dialects), this area shares one common cultural foundation. Music, customs, architecture, food are basically identical in Bavaria, Bohemia and Upper Austria, and transcend linguistic and national lines. Indeed there is a much greater cultural difference between Slovakia and Bohemia on the one hand, despite the almost identical languages, than compared between Bohemia and Bavaria or Austria on the other.

Celtic Europe (click to enlarge). |

Reconstruction of a Celtic village near Chrudim, Czech Republic. |

Roman villa in Malta. |

Roman military banner. |

Roman Empire in 117 AD (click to enlarge). |

The Barbarians started to control the area north of the Roman border and, toward the end of Antiquity, the Celtic threat that had persisted for many centuries was replaced by a new threat: the Barbarians. The reasons for this immense migration of people were the push of other Asian tribes from the east, and also an expanding population that led to the need for new land. Often, the prize was to be found on Roman territory. The Roman Empire was in deep decline by this time and its immense border could no longer be adequately secured. That left its outlying regions an easy prey.

Post-Roman Europe (late 5th century AD) (click to enlarge). |

Coat of arms of Bavaria. |

Merovigian Kingdom 481-814 AD Click to enlarge. |

Unlike Bavaria, Bohemia was not part of the lands ruled by the Merovingian Kings. The area of modern-day Bohemia was ruled by the Marcomanni and other Suebic groups. The Romans forces pushed them out of Germany and they took refuge in Bohemia, taking advantage of the natural defenses provided by the surrounding mountains. The Marcomanni maintained a strong alliance with neighboring tribes, the Lugii, Quadi and others. The alliance was often in conflict with the Roman Empire, such as in the second century when they fought Marcus Aurelius. After the fall of Rome, in the 5th century many of these tribes left and and eventually re-settled as far away as Spain and Portugal. The Vandals and the Alans left in 409 AD and the Marcomanni in the mid-5th century. Atilla the Hun invaded the area in the 5th century, causing chaos and an influx of new population from the east. At the end of the 5th century, the Langobardi and the Thuringians sailed up-river along the Elbe, settled util the first half of the 6th century, then continued to move to an area along the Danube and in 568 AD to Italy. The Slavic tribes arrived most likely in the second half of the 6th century, with a second wave following in the 7th century. Most of the Germanic tribes had left by that time, and they found the area populated only by remaining Langobardi. The Slavic language began to replace the older Germanic, Celtic and Sarmatian ones. These were the ancestors of modern-day Czechs.

Coat of arms of Bohemia (early Přemyslid dynasty). |

The names "Bavaria" and "Bohemia" are both derived from the Latin name of the Boii Celtic tribe that had inhabited this area in the past. The historians Tacitus and Strabo referred to this area as Boiohaemum ("Home of the Boii"). The second component of the name is a Germanic word for "home", related to modern German "Heim", hence the term "Boii-home". The term "Bavarian" derives from the Latin Baiuvarii, translating as "Men of Baia", which may indicate Bohemia, the homeland of the Celtic Boii.

Christianity was implemented in Bavaria was in the early-8th century. It appeared first in the early 9th century in the neighboring Bohemia and became dominant later, in the 10th-11th century. A period of common history started, which would last for more than 1000 years until present day. The Duchy of Bohemia, along the Duchy of Bavaria were now both under control of the Merovingian Kings from the Frankish Empire, and would both later become parts of the Holy Roman Empire.

Coat of arms Tyrol. |

Tyrol Castle. |

Coat of arms of Upper Austria. |

Holy Roman Empire around 1000 AD Click to enlarge. |

Historic flag of Bohemia, Upper Austria, and Tyrol. |

Bavaria was one of the stem duchies (Stammesherzogtum of the Holy Roman Empire from the time of its founding and included, at the time of the forming of the empire, the moldern-day regions of Tyrol, Styria, and Upper Austria. The Duchy of Bohemia became part of the Holy Roman Empire at the beginning of the 11th century. Tyrol achieved Imperial immediacy in 1138, after the deposition of the Bavarian duke Henry the Proud, and formed a state of the Holy Roman Empire in its own right.

In the 10th century, Bavaria was a large kingdom, extending far to the east and south, as far as modern-day Carinthia, Lower Austria and Upper Italy, but the very centre of it was on the Danube. In the 10th and 12th centuries it became the duchies of Bavaria, Carinthia and Austria. The ducal seat was Regensburg. Munich became capital in 1255.

Coat of arms of Bohemia. |

King Charles IV. |

King Wenceslas IV. |

Emperor Sigismund. |

Jan Hus. |

Poor Sigismund gets a bad rap with the average Czech, even after 600 years, because 40 years of Communist propaganda portrayed him in history textbooks as something of a Medieval Hitler, tormenting the poor Protestant rebels.

Not to be forgotten are the Ashkenazi Jews who spread throughout Central and Eastern Europe, wgho formed a very important part of the population until recent times. Their spread started during the 13th century with the expulsions from England (1290), France (1394), and parts of Germany (15th century). They established communities throughout Central and Eastern Europe, which had been their primary region of concentration and residence, evolving their own distinctive characteristics and diasporic identities. People such as Sigmund Freud, Gustav Mahler, Albert Einstein, Franz Kafka and Leonard Bernstein belonged to this ethnic group.

Coat of arms of Munich. |

In Bohemia, following the Hussite Revolution, things went generally downhill politically. The strong country that Charles IV had built was in shambles, decisive leadership nonexistent. Sigismund, Brother of Wenceslaus IV, ruled the kingdom 1419–1437. After him came the first Habsburg, Albert II of Germany, having married Elisabeth of Luxemburg, Sigismund's daughter and heiress in 1422. Two Habsburg kings ruled the Kingdom of Bohemia until 1457. The Habsburg dynasty returned to the Czech throne in 1526 and ruled the country until 1918. Among them were 13 Holy Roman Emperors. Among them were memorable figures such as Rudolph II, Empress Maria Theresa and

Empress Maria-Theresa. |

Emperor Rudolf II. |

Habsburg Empire in 1700 Click to enlarge. |

Habsburg coat of arms. |

A degree of religious freedom and independence was maintained in the Habrburg Monarchy until 1620, when the Battle of the White Mountain took place. An army of 30,000 Czechs and mercenaries under the command of Christian of Anhalt were defeated by 27,000 men of the combined armies of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles Bonaventure de Longueval, Count of Bucquoy, and the German Catholic League under Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly. The battle marked the end of the Bohemian period of the Thirty Years' War and decisively influenced the fate of the Czech lands for the next 300 years. Consolidation of power by the victorious side and religious persecution started almost immediately. With the force defending Prague destroyed, Tilly entered Prague and the revolt collapsed. King Frederick with his wife Elizabeth fled the country, and many Czechs welcomed the restoration of Roman Catholic rule. Forty-seven leaders of the insurrection were put on trial, and twenty-seven of them were executed in Prague's Old Town Square. An estimated five-sixths of the Czech nobility went into exile soon after the Battle of White Mountain, their properties confiscated and bestowed upon those tho helped the winning side. The Emperor ordered all Calvinists and other non-Lutherans to convert to Roman Catholicism or leave the Kingdom in three days. The Emperor also ordered all Lutherans (most of whom had not been involved in the revolt) to convert or else leave the country. Most people converted, but a significant Protestant minority remained. But at the same time, the exodus was massive. Before the war about 151,000 farmsteads existed in the Lands of Bohemian Crown, while by the year 1648 only 50,000 remained. At the same time the number of inhabitants decreased from three million to only 800,000. At the same time, a great deal of money was invested by the Habsburg government in the coming decades in the construction of churches, cathedrals, monasteries, chapels etc. The flip-side of this rather grim period of Czech history is that some of the most beautiful Baroque architecture found anywhere in the world dates to this time.

Coat of arms of the Austrian Empire (1804-1867). |

Coat of arms of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1867-1918). |

Bavaria in 1808 (lick to enlarge). |

Habsburg Empire in 1700 AD (Click to enlarge). |

Bavaria became a constitutional monarchy, ruled by a King and a parliament. Constitution was declared in 1818. The parliament was to consist of two houses; the first comprising the great hereditary landowners, government officials and nominees of the crown; the second, elected on a very narrow franchise, comprising representatives of the small land-owners, the towns and the peasants. By additional articles the equality of religions was guaranteed and the rights of Protestants safeguarded. King Maximilian ruled till his death as a model constitutional monarch. He was succeeded in 1825 by his son Ludwig I. Ludwig I was an enlightened patron of the arts and sciences. He transferred the Landshut university to Munich. Ludwig I had a good architectural taste and transformed into one of the most beautiful cities of the continent. He abdicated during the revolutionary year of 1848, and was succeeded by his son, Maximilian II. Before his abdication, he wrote a proclamation promising firm commitment of the Bavarian government the cause of German freedom and unity. Maximilian II followed that guidance, accepting the authority of the central government at Frankfurt. That move, however, made Prussia henceforth the enemy of Bavaria instead of Austria. During the rise of Prussia to prominence, Bavaria was allied with Austria, fought alongside with it in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, and was defeated along with it. Maximilian was succeeded on in 1864 by his son Ludwig II, a youth of eighteen at the time. The Bavarian government found it necessary to become part of the Prussian commercial treaty with France, signed in 1862. Bavaria did not belong to the North German Federation of 1867, but when France attacked Prussia in 1870, the southern German states Baden, Württemberg, Hessen-Darmstadt and Bavaria joined Prussia and ultimately joined the Federation, which was renamed German Empire (Deutsches Reich) in 1871.

King Ludwig II. |

Neuschwanstein Castle. |

Hohenschwangau Castle. |

Linderhof Palace. |

Herrenchiemsee Palace. |

Ludwig's Hall Of Mirrors. |

Louis' Hall Of Mirrors. |

Planned Falkenstein Castle. |

Tyrol Castle. |

Original County Of Tyrol. |

Holy Roman Empire c. 1600. |

Gulasch della Val Pusteria (Citrus-Infused Goulash From South Tyrol). |

Moreover, the dumpling is a deeply rooted part of folk culture and, like many other culinary objects, resonates with a profound sense of local identity. Dumplings are hardly on a par with haute cuisine or other complex culinary traditions, and there is much humor and self-deprecation in the culinary writing on dumplings. This is where the Austrian promotional dumpling campaign becomes very heart-warming. In 2006-2007, Lufthansa even put blood-sausage dumplings on the menu in first-class flights (right alongside with caviar and truffles).

|

Gnocchi |

Gnocchi are small Italian dumplings made from semolina flour, wheat flour, finely-grated potatoes or bread crumbs. Gnocchi are small pieces of dough, usually round in shape, which are boiled in water or broth and then served with various sauces. They are "the mother of all dumplings", in that they were introduced by the Roman Legions to every corner of the empire across the European continent. In the past 2000 years each country developed its own specific type of dumplings, with the ancient Gnocchi as their common ancestor.

Gnocchi are an ancient dish, prepared with different flours: wheat flour, rice, potatoes, and even dry bread, potatoes or vegetables varie. The more common variety prepared in Italy today are made from potatoes, but the ones made from a simple mixture of flour and water are also very popular. Others, often nicknamed "Roman", are still prepared with semolina flour as in the Roman time. Still others are made from corn flour. Also used are a variety of other ingredients based on local traditions. Gnocchi can be served as the first course of a traditional Italian dinner (primo piatto), as is the tradition in almost all of Italy, as a main dish (piatto unico)or as a side dish (contorno).

Vegetables and herbs are often added to gnocchi. Small gnocchi, called zanzarelli, can have green color from the addition of chard and spinach, or yellow from the addition of pumpkin or saffron. Green zanzarelli (Zanzarelli verdi) come from Milan, from the Castello Sforzesco and date back to the 15h century to the rule of Ludovico Maria Sforza detto il Moro, Duke of Bari and Duke of Milan. They were small dumplings made with almonds and cacio lodigiano, the precursor of the modern-day grana padano and parmigiano reggiano cheese. They were served to the court in large bowls swimming in broth, in celebration of military victories and for weddings. The bowls were brought before the Duke and, in a kind of self-service, diners approached with their own plates to serve themselves. Adding spinach, saffron and eggs to the broth gave it a golden color, which the Duke obviously liked as it symbolized money. A simplified 21st century version of the recipe is:

Zanzarelli verdi:

Ingredients:

- 1 liter of broth

- 3 tbsp of bread crumbs

- 3 tbsp of grated Parmesan cheese

- 2 eggs

- 20-25 g almonds, blanched and finely chopped

- 400 g spinach

- 1 pinch of nutmeg

- 1/2 tsp of saffron

- 10 g butter

- salt and pepper, to taste

Preparation:

- Clean the spinach, wash thoroughly in cold water, drain, adn chop finely.

- Brown the chopped almonds in a pan with a little butter, then let cool.

- Place the bread crumbs in a bowl, add the almonds and chopped spinach, the parmesan cheese, eggs and a pinch of salt, pepper and nutmeg. Mix the ingredients until the mixture is quite soft.

- Dissolve the saffron in the hot stock, and bring the stock to a boil. Spoon a little of the dough at a time, forming the zanzarelli dumplings. Throw them in the boiling stock, a few at a time. Alternatively, using a pastry bag with a plain nozzle, drop the dough into the boiling broth, cutting it periodically with a knife. Cook for about 3 minutes. Remember that fresh pasta cooks fast.

- YIELD: 4-6 people.

Then there are malfatti, little gnocchi-like morsels made of ricotta cheese and spinach, which developed during the seventeenth century from zanzarelli by substituting flour, water and eggs for almonds and bread crumbs.

Malfatti:

Ingredients:

- 500g spinach leaves, washed, dried and chopped

- 250g ricotta cheese

- 1 large egg

- 1/4 nutmeg, freshly grated

- 125g parmesan cheese, grated, plus extra for serving

- Salt and pepper, to taste

- 40gr Tipo "00" flour (fine-grained wheat flour)

- 200g fine semolina flour

- 100g butter, for garnish

- 20 leaves fresh sage, for garnish

- 1/2 lemon

Preparation:

- Cook the spinach in a large, deep pan over a medium heat for 2-3 minutes until wilted. Drain and squeeze out all the water. Set aside to cool.

- In a large bowl, mix together the ricotta cheese and the "00" flour. Stir in the spinach, beaten egg, the parmesan cheese, the nutmeg, salt and pepper. Stir well until mixed.

- On a surface floured with half of the semolina flour, roll the dough into 25 balls, each the size of a walnut. Place the balls on a tray floured with the rest of the semolina flour.

- Bring a large pot of salted water to a boil, and throw in the malfatti a frew at a time. Cook for 2-3 minutes, until they float to the surface. Remember that fresh pasta cooks fast. Drain and keep warm in the pan.

- In a small frying pan, melt the butter and gently cook the sage leaves for 30 seconds. Squeeze the lemon juice in and mix well.

- Place the malfatti onto plates, ptop with the warm butter sauce and sprinkle with the extra parmesan cheese.

Potato gnocchi spread throughout Italy in the 1880s. They are a hearty dish, usually served with meat sauce or ragú. One option is to serve it with Ragú alla Bolognese. One very special recipe is Strangolapretti (or Strozzapretti), spinach and bread gnocchi from South Tirol. The name literally translates as "Priest Chokers", referring to a rather gluttonous member of the Catholic clergy who stuffed themselves with this dish, because he loved it so much, to the point of suffocating himself. Other, less threatening dishes, include Potato gnocchi can be served with tomato sauce and mozzarella (Gnocchi all Sorrentina).

Beside potato gnocchi, other recipes include Gnocchi Alla Romana made with flour, grated parmesan cheese, eggs and butter, and Gnocchi Verde Carduta Del Formaggio made with spinach and served with blue cheese sauce.

Ragú with gnocchi |

Ingredients:

- 3 lbs russet potatoes

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 egg, extra large

- 1 pinch salt

- 1/2 cup canola oil

Preparation:

- Boil the whole potatoes until they are soft (about 45 minutes). While still warm, peel and pass through vegetable mill onto clean pasta board.

- Set 6 quarts of water to boil in a large spaghetti pot. Set up ice bath with 6 cups ice and 6 cups water near boiling water.

- Make a well in center of potatoes and sprinkle all over with flour, using all the flour. Place egg and salt in center of well and using a fork, stir into flour and potatoes, just like making normal pasta. Once egg is mixed in, bring dough together, kneading gently until a ball is formed. Knead gently another 4 minutes until ball is dry to touch.

- Roll baseball-sized ball of dough into 3/4-inch diameter dowels and cut dowels into 1-inch long pieces. Flick pieces off of fork or concave side of cheese grater until dowel is finished. Drop these pieces into boiling water and cook until they float (about 1 minute). Meanwhile, continue with remaining dough, forming dowels, cutting into 1-inch pieces and flicking off of fork. As gnocchi float to top of boiling water, remove them to ice bath. Continue until all have been cooled off. Let sit several minutes in bath and drain from ice and water. Toss with 1/2 cup canola oil and store covered in refrigerator up to 48 hours until ready to serve.

Gnocchi spread through the Roman empire and became Spätzle north of the Alps, in modern-day Austria, southern Germany, Switzerland and southern France. Around the city of Nice, there are Gnocchi de tantifla a la nissarda made from with potatoes and wheat flour. There is also a variation made with made with potatoes, wheat flour, eggs and Swiss Chard, called in affectionately in French La merda dé can, which translated literally as "Dog Shit", due to its dimensions (not taste). In Paris, there are also Gnocchis à la parisienne, that are very similar to traditional Italin gnocchi and seem to be a modern-day adoption of an italian dish in a cosmopolitan city.

|

Ravioli |

Ravioli are a filled pasta dumpling, composed of a filling sealed between two layers of thin egg pasta dough. They are commonly square, though other shapes exist, including the semi-circular mezzelune. Other related filled pastas include the ring-shaped tortellini and the larger tortelloni. All of them can be served served either in a broth or with a pasta sauce.

Ravioli Marinara |

Ravioli di faraona |

Classic spinach and ricotta ravioli from Lazio |

Ligurian ravioli in creamy sauce with nuts. |

Zillertaler Krapfen |

Spinach And Ricotta Ravioli |

Ingredients for 40 ravioli:

- 250 g fine-grained flour tipo "00"

- 2 large eggs plus 1 egg yolk

- Salt and pepper, to taste

- 250 g fresh spinach

- 125 g Cottage cheese

- 50 g Parmesan cheese

- 1/4 tsp Nutmeg

Preparation:

- Make the dough. Sift the flour and make a pile it on the work surface. Form a small hollow in the center and break the eggs into it, one at a time. Add the salt. Starting from the inside, mix the eggs with a fork or a spoon, then continue by pusing flour from the edges into the center. When a mixture forms, continue with hands, mixing in all the flour from the work surface. When a dough forms, work it with both hands, folding it in half, then into quarter, knead with the palms of both hands until flat, then repeat the folding process again and again. The dough needs to be completely smooth. If it is hard, add 1-2 tbsp of warm water and continue to knead until smooth and compact result. When the dough is ready, wrap it in plastic wrap and let rest for about 1 hour in a cool, dry place.

- Meanwhile, prepare the filling. In a blender, combine the ricotta, Parmesan, nutmeg, salt and pepper. Mix well. Sauté the spinach in a pan, pat dry and add to the blender. Mix well again until the mixture is smooth and compact.

- Roll the dough into a thin sheet and divide it in two strips about 10 cm wide.

- Make the ravioli: Place small portions of dough well apart, spoon the spinach and ricotta ravioli mixture in even intervals onto one of the sheets of dough, 1/2-1 tbsp at a time. When finished, overlap the two sheets of dough on each other, so that the two sheets come together. Take care to remove any air bubbles that may remain between the two sheets.

- Using a wheel cutter, cut squares about 4x4 cm. The recipe should yield about 40 ravioli. Coil the ravioli immediately, or place them well spaced on a tray lined with parchment paper and freeze them.

- Cook the ravioli: boil plenty of salted water. Start dropping the ravioli in twos and threes into the water using a slotted spoon. Fresh pasta cooks quickly. The ravioli are ready when they float to the surface. Remove them from the water with the slotted spoon and place in a large bowl.

- Serve in the bowl with the sauce of your choice. One suggestion is simply melted butter and sage, for a basic but exquisite, classic Roman taste.

|

Tortellini |

Tortellini, and their larger relatives the tortelloni, are a filled pasta dumpling, composed of a filling sealed between two layers of thin egg pasta dough, shaped into a ring. They They originate from the northern Italian region of Emilia, particularly Bologna and Modena. They are traditionally stuffed with a mix of local meats (pork loin, prosciutto) or cheese. They are usually served in broth, either of beef, chicken.

Unlike ravioli, the origin of which is well documented, the origin of tortellini is unknown and subject to legends and speculations. They probably originated in the 15th-16th centuries.

Tortellini in brodo (tortellini soup) are a classic in Emilia. There is a similar dish in Romagna using Cappelletti. Tortellini and Cappelletti are visually identical, with the difference being in the filling. Cappelletti are filled only with cheese, while Tortellini are filled with meat. They are both typical Christmas Eve pasta courses.

Tortellini:

Ingredients:

- Egg and flour dough, same as for ravioli

- Meat broth, chicken or beef

- 100g pork sirloin (3,5oz)

- 100g prosciutto crudo (3,5oz)

- 100g Mortadella (3,5oz)

- 150g Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, grated (5oz)

- 1 large egg

- 3 pinches grated nutmeg

Preparation:

- In a food processor, mix all the ingredients until they become a paste.

- Cut the dough in 4-cm (1 1/2 in) wide squares. Place a bit of the filling in the middle of the pasta square. Fold it in a triangle shape, close the edges, then wrap it around the index finger and press the two ends one upon the other. Use a drop of water if the dough fails to stick.

- Boil the tortellini in a good homemade broth (beef or chicken) until they float to the surface (al dente). Fresh pasta cooks quickly, depending on how thin the dough is.

|

Spätzle |

Spätzle are the Austrian and German cousins of gnocchi. They are small dumplings made of eggs and flour. They may be called Spätzli, Nockerln or Knöpfle in parts of Germany and Austria; Knöpfli in Switzerland; csipetke, nokedli, galuskangs in Hungary; and halušky in Slovakia.

Knöpfli type of spätzle. |

Thin commercial type Spätzle. |

Spätzle can be served as a side dish to various goulashes and meat dishes with abundant sauce,

such as chicken paprikash, Zwiebelrostbraten, Sauerbraten or Roulade. In Hungary spätzle are often

used in soups. Spätzle also are used as a primary ingredient in savory dishes such as:

Käsespätzle in a ski restaurant on the Hintertux Glacier. |

Gaisburger Marsch stew. |

Schwäbische Krautspätzle. |

Schwäbische Krautspätzle. |

Spinatspatzeln from Tyrol. |

Other Austrian-Italian fusion dishes include Spätzle Parma (Spätzle cooked with sour cream and grated parmesan cheese), and Spätzle al Pesto (served like gnocchi with pesto sauce).

Spätzle also exists in sweet forms, such as Kirschspätzle (Spätzle mixed with fresh cherries, dressed with clarified, browned butter, sugar and cinnamon and/or nutmeg), or Apfelspätzle (Spätzle with grated apples in the dough, dressed with clarified, browned butter, sugar, and cinnamon).

Käsespätzle in Tirol |

Käsespätzle |

Ingredients:

- 1 lb flour

- 5 eggs

- 150-200 ml water

- Salt

- Special tools for purists: Spätzle board and scraper

Preparation:

- Mix all ingredients in a bowl and beat until the dough begins to bubble. Traditionalists can use their hands, the rest use a dough mixer. The dough has the right consistency when it drips slowly from a spoon without tearing. Otherwise, add more water or flour.

- Fill a large pot with water and bring to a boil, add plenty of salt. Prepare a bowl and a strainer.

- Wait for the water to boil and start cooking the spatzel in batches. Spätzle-gurus will use the Spätzle board: briefly moisten the board and scraper in the pot, then spread about 2 tablespoons of the dough thin over the board. Hold the board at the surface of the boiling water and cut the dough with a straight scraper into small pieces and let them fall in the water. Normal people will simply spoon teaspoon-size chunks of the dough into the water. The final product will taste the same.

- The spätzle are done when they float back to the top. Remove with a slotted spoon and drain in the stand-by bowl.

- Repeat batches until all dough is finished.

Bryndzové halušky from Slovakia. |

Hungarian Nokedli. |

Paprikáscsirke (Chicken Paprikash) from Hungary. |

Spätzle made it far into Eastern Europe as well, beyond the Austro-Hungarian Empire. There are similar dishes in Romania (găluşte), Serbia (galuški), Ukraine (галушка), and Lithuania (virtinukai).

Moving back to Austria, Tiroler Speckknödel are tennis-ball size, round bread-and-flour dumplings made from flour dough with added herbs and smoked bacon. These are substantial dumplings. Calorie-wise, traditional Tyrolean dumplings are serious business: beside smoked bacon, home-made smoked pork sausage (Kaminwurzn), cured pork or lard can be used. The dumplings can be boiled in salted water and served simply on a bed of sauerkraut, or as a side dish to goulashes or roasted pork. They can also be cooked in a strong beef broth and served in it as a soup (Speckknödelsuppe).

|

Tiroler Speckknödel (Tyrolean Dumplings With Bacon) |

Ingredients:

- 6 stale bread rolls or baguette

- 1 egg

- 250 ml milk

- 1 onion

- 1 bouquet of parsley

- Salt, pepper

- Caraway seeds

- 60 g butter

- 60 g flour

- 150 g smoked bacon, cured pork, smoked pork sausage i.e. Landjäger or dark salami

Preparation:

- Chop the onion and fry it briefly in the butter with the chopped parsley.

- In the meantime, warm the milk and cut the bread into little pieces. Chop the sausages into little cubes.

- In a large bowl, mix the bread with the warm milk and egg. Add the fried onion, spices, sausage and parsley and make a coarse dough. Form dumplings of about 5 cm in diameter.

- Boil salted water. Add the dumplings and boil them for about 15 to 20 minutes.

- YIELD: serves 3

Speckknödelsuppe from Tyrol. |

Leberknödelsuppe from Vienna. |

Leberknödelsuppe at Bei Otto in Bangkok. |

Jewish Matzah Balls in chicken soup. |

Czech Hovězí polévka s játrovými knedlíčky. |

The Central European soups with dumplings in them seem to be a cross-pollination with Italy, where soups with gnocchi, ravioli, tortellini, Cappelletti, etc. are very common.

Moving from Austria further north into Germany, Bavarian dumplings resemble Tyrolean dumplings in shape, but unlike the Tyrolean species these are almost health-food! Lard and bacon are typically not used. They can be served as a side dish with pork roast or goulash. Or, to properly lubricate the arteries, they can be sliced and fried in butter until brown with a scrambled egg thrown in.

|

Bayrische Semmelknödel (Bavarian Bread Dumplings) |

Ingredients:

- 1/2 lb stale baguette (1-2 days old)

- 2 tbsp butter

- 1 cup milk

- 2 eggs

- 1 tbsp flat parsley, finely chopped

- 1 onion, finely chopped

- 1/2 tsp salt

- Dash pepper

Preparation:

- Cut the baguette in small cubes and place in a large bowl.

- Bring the milk to a boil, pour over the baguette and let soak for 10 minutes.

- Meanwhile, fry the onion in butter until soft. Add parsley.

- When the bread has finished soaking, combine the fried onion, eggs, salt and pepper.

- Mix well using hands. With wet hands, form round, tennis-ball-size dumplings.

- Boil in salt water for 20 minutes.

- Remove finished dumplings with a slotted spoon. Let drip shortly in a sieve. Place in a serving bowl and serve.

|

Bayrische Kartoffelknödel (Bavarian Potato Dumplings) |

Bavarian potato dumplings are made of boiled and raw potatoes and breadcrumbs. They are round and the same size as their bread-dumpling siblings. They can be served with goulashes, roasted pork etc. Sometimes, before boiling, a crouton is placed into the center of the dumpling. Over the border in the Czech Republic, they are called Jihočeské Bosáky.

Ingredients:

- 1 1/2 potatoes

- 1 egg

- 4 tbsp breadcrumbs

- Salt

Preparation:

- Peel half of the potatoes and boil in salted water for 20 minutes.

- Peel the other half of the potatoes and finely grate. Wrap in a dish towel and, over a bowl, squeeze out as much liquid out as possible, saving the liquid. After a few minutes, the potato starch will settle on the bottom of the bowl. Carefully skim the water, then mix the starch residue with the potatoes.

- Add the egg, breadcrumbs and a dash or two of salt.

- Drain the boiled potatoes and finely grate. Mix with the raw potatoes.

- Coat hands lightly with flour and form 6 round dumplings, approximately the size of a tennis-ball

- Bring salted water to a boil in a large pot. Reduce heat to medium and boil the dumplings for 20 minutes. They are ready when they float to the surface.

- Remove finished dumplings with a slotted spoon. Let drip shortly in a sieve. Place in a serving bowl and serve

|

Käseknödel (Cheese Dumplings) (All credit to Eliza from Toprecepty.cz). |

Preparation of Tyrolean Cheese Dumplings (All credit to Eliza from Toprecepty.cz). |

Preparation of Tyrolean Cheese Dumplings (All credit to Eliza from Toprecepty.cz). |

Ingredients:

- 1/2 lb stale bread rolls or baguette

- 1 cup milk

- 1/2 lb hard cheese, grated (Emmentaler, Gruyère, Bergkäse, Parmesan, Pecorino )

- 1 onion, chopped

- 3 eggs

- 1 tbsp flour

- 2 tbsp parsley, finely chopped

- 2 tbsp chives, chopped

- Salt For garnish:

- 5 tbsp butter

- 4 tbsp hard cheese, grated (Emmentaler, Gruyère, Bergkäse, Parmesan, Pecorino )

Preparation:

- Cut baguette into small pieces, place in a large bowl and soak in the milk.

- Cut the onion and cheese into small pieces. Fry onion in butter until brown.

- Mix together the soaking baguette, flour, cheese, and onion, and work a thick dough.

- Using hands lightly coated with flour, form round tennis-ball size dumplings.

- Boil salted water in a large pot. Cook dumplings for approximately 15 minutes.

- Garnish with melted butter and grated cheese.

|

Houskové Knedlíky (Czech Bread Dumplings) |

Moving east, modern-day Czech and Austrian savory dumplings differ in shape from their Bavarian and Tyrolean relatives. While in Tyrol and Bavaria, dumplings are cooked as individual spheres the size of a tennis ball, in the Czech Republic and in the rest of Austria, dumplings evolved in a different direction. They are shaped into cylinders of dough 6-12 inches long, boiled whole and sliced into 1/2-inch slices before serving. Although sliced cylindrical dumplings predominate in the Czech Republic, in the southern part there exist round individual dumplings as well: bosáky, drbáky, and chlupaté knedlíky. This is mainly in the southern part of the Czech Republic along the border with Bavaria.

Bavarian Liver Dumpling, the closest living relative to the Medieval Central European dumpling. (All credit to Fiammi from Chefkoch.de) |

Make dumplings as follows. Chop veal and mix with egg yolks, add spices and parsley. Fry on a pan, in lard of butter, add sweet ot shot spice.The closest living relatives to the medieval Central European dumplings seem to be some of the meat dumplings from Tyrol or Bavaria, such as the Bavarian Liver Dumpling (Bayerische Leberknödel). Flour was not used in Central European dumplings until the 17th century, exactly like in this dumpling. It is made of meat, eggs, onion, garlic, lemon peel, and seasoned with marjoram, salt and pepper. (The cubed bread roll is a 17th century addition.) The dumpling is fried, not boiled. The only difference is size: the Medieval dumpling would have been smaller, about like the Italian Gnocchi, this dumpling is large, the size of a tennis ball.

Modern-day sweet Buchty. |

As a side note, it is interesting to note that in northern Germany, the word for dumpling is Kloss (pl. Klosse), pointing to the fact that cultural differences in Central Europe run more between the north and the south, with Austria, Bavaria, Bohemia and Tyrol clearly belonging jointly to the southern part.

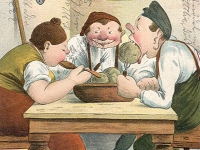

19th century dumpling eater (Courtesy of Museum Cheb). |

19th century dumpling eater (Courtesy of Museum Cheb). |

Whole Czech-style bread dumpling. |

Whole Czech-style bread dumpling. |

Vienna-style goulash from Prague, served with Czech-style bread dumplings. |

Pork roast, sauerkraut and Czech-style bread dumplings.. |

The foundation of every modern-day bread dumpling is coarse flour, lukewarm milk (or water), yeast, eggs (or egg yolks), salt, and cubed stale white-bread rolls i.e. houska (Kaisersemmel), rohlik (Stangerl), or veka (Weckerl, the Czech and Austrian equivalent of New Orleans French Bread). As with other dumplings, the choice of flour is key to success. Using typical "all-purpose flour" off the shelf of most American supermarkets will yield disastrous results. The resulting dumpling will be slimy, with the consistency of amorphous brain matter. Coarse unbleached flour has to be used. It is readily available everywhere in Central Europe, and in any decent gourmet store in the United States. The problem in finding proper flour in the United States for this type of dumplings are the different classifications for flour types. Germany, France and Poland classify flour types based on the amount of ash obtained from a set amount of dry mass of the flour. Czech flour types are determined by grain size: Extra soft wheat flour (Výběrová hladká mouka, Type 00), Soft wheat flour (Hladká mouka), Fine wheat flour (Polohrubá mouka), Coarse wheat flour (Hrubá mouka), and Farina wheat flour (Pšeničná krupice). In the United States and the United Kingdom, no numbered standardized flour types are defined. Very aproximately, Hrubá mouka corresponds to something like white whole wheat flour in the U.S.

In the section below, we present 3 recipes that span 3 centuries: from 1845, 1924 and 2007.

Magdalena Dobromila Rettigová. |

Magdalena Dobromila Rettigová. |

Preparation:

- Cut the bread rolls into small cubes and fry in [clarified] butter until golden-brown. [Dry on paper towels and] let cool.

- In a bowl (an electric dough mixer in the 21st century), mix and stir fresh butter. Add six eggs, one at a time. Add a handful of flour after each egg and a tablespoon of cream. Add salt and mix properly.

- Add the fried bread cubes and continue to work the dough. Add enough flour to make the dough properly firm. Rettigová's test was to slap it with her hand to see if the dough stuck to the hand or not. Proper dough did not stick.

- Form individual balls and boil [in salted water for about 20 minutes].

- Remove dumplings from the water, tear into quarters, top with ground bread crust and melted fresh butter and serve.

- [Note that her recipe still assumed a round dumpling, not a cylinder.]

Her alternate recipe was:

- Dissolve 4 egg yolks in water and mix until they begin to foam. Add salt and 1/2 kg (approx. 1 lb) flour and form a dough.

- Cut 2 rolls into small cubes. Place cubes on top of dough, carefully pour 1/2 to 1 cup of melted butter over them and allow to rest for 2 hours.

- Before boiling the dumplings, roll bread cubes into the dough, and work the dough properly.

- Create nice size dumplings and boil uncovered [in salted water, for about 20 minutes].

- Remove dumplings from the water, divide into halves using a fork, top with ground bread crust and melted fresh butter and serve.

1924 recipe by Marie Janků-Sandtnerová

Ingredients:

- 500 g flour (approx 2 cups), sifted

- salt

- 1/4 l milk (approx 1 cup)

- 1/8 l water (approx 1/2 cup)

- 2 eggs yolks

- 300 g butter, melted, for topping

- 200g bread rolls, ground

Preparation:

- Stir together the egg yolks and the milk.

- Mix together the flour and the salt. Continue to stir and add the cold water and the milk. [In the 21st century, use a dough maker for this.] Prepare a reasonably firm dough.

- Cut the bread rolls into small cubes and fry them in butter. [Dry on paper towels and] let cool. When cool, add them to the dough, and let rest for 1/2 hour.

- Divide the dough into even portions. On a flour-coated board, make long cylindrical dumplings.

- Boil in salted water 15-30 minutes. During boiling, lift with a wooden spoon to prevent sticking. Turn them upside down halfway through the boiling process.

- Remove finished dumplings from the water and place on a cutting board. Using a sharp slicing knife or a strong tread, slice into even slices 1 cm thick (approx. 1/3 in). [In the 21st century, use our dumpling cutter.]

- Top with the melted butter and the fried breadcrumbs, and serve.

It is interesting to note the evolution here. Rettigová in her 1845 recipes still describes Czech flour dumplings as round balls, while Sandtnerová in her recipe published 79 years later already speak of dumplings as long cylinders that are boiled, then sliced.

2007 Recipe by Jiří Dienstbier (from a time emancipation reached the kitchen, and guys cook to impress the hell out of chicks).

Ingredients:

- 1 kg (approx. 4 cups) coarse flour

- 8-10 stale white bread rolls, cut into cubes

- 5 egg yolks (or whole eggs)

- Whole milk

- 1 tsp salt

- Special tools: dumpling cutter

Preparation:

- Sift the flour into a bowl. Mix with the salt and place in a large bowl.

- Create a shallow depression in the middle of the dough, and pour in the egg yolks. (If using whole eggs, the whites will make the dumpling firmer.)

- Using a wooden spoon (or a bread-dough maker) mix the ingredients, while adding milk. Add enough milk to create a dough of desired consistency. The formation of air bubbles in the dough is desirable. Traditional recipes called for hand-mixing for up to half an hour. If mixing by hand, 10 minutes of elbow grease will suffice. Work the dough until it is smooth and shiny but no longer sticky.

- Add the bread subes; as much as possible, as much as the dough will absorb. Mix well. Cover the mixing bowl with a dish towel, place in a moderately warm place, and let rest for 2 hours.

- Boil salted water in a large stockpot.

- With hands dusted in flour, form cylinders approximately 3 by 6 inches in size. Add the dumplings to the briskly boiling water and boil approximately 20-25 minutes, making sure they do not stick to the bottom or to each other.

- During the boiling, the dumplings will float up to the surface. Cook 10 minutes, turn over and cook another 10 minutes to ensure they are evenly cooked.

- Remove from the water and slice into one of them to make sure the dumplings are cooked through. If desired, pierce dumplings with a fork to help release steam inside.

- To serve, slice dumplings into 1/2-inch slices with a very sharp knife, thread or a dumpling cutter.

|

Serviettenknödel (Bread Dumpling In a Dish Towel) |

Serviettenknödel is a family of coarse-grained bread dumpling, in which the ratio of bread cubes and flour is reversed as compared to the regular flour dumpling. There is more of the cubed bread in these dumplings than flour. This makes them more prone to breakup during cooking, as there is less of the sticky flour matrix holding the bread pieces together, hence the need to wrapping them in a dish towel. In some recipes, there may not be any flour at all.

Here are two recipes for Vienna Serviettenknödel, both claiming to be original. The

first recipe one produces a round dumpling that is served sliced in half. The second one

produced a long cylindrical ("Czech-style") dumping, that is served cut in slices.

Serviettenknödel recipe from Prague

Ingredients:

- Several stale bread rolls, cut into small cubes

- 2 eggs

- 1/4 l milk (approx 1 cup)

- Butter

- 1/2-1 cup coarse flour

- Salt

- 1 medium onion, finely chopped

- 1 bunch parsley, finely chopped

- Special tools: Large steamer.

Preparation:

- Cut the stale bread into small cubes, place in a large bowl and leave to dry for several hours. Do not toast them in the oven.

- Break the eggs into a small bowl. Add the milk and salt, and whip.

- Pour the mixture over the bread cubes, and mix carefully not to break up the bread.

- In a saucepan, melt a dollop of butter and sauté the onion and parsley. When the onion turns translucent, add the onion and parsley to the dough. Add the flour and carefully mix again.

- Allow to rest of 1 hour, them carefully mix again.

- Form individual, round, tennis-ball size dumplings. Melt some more butter and baste the dumplings on all sides. Spread paper towels or napkins, generously lined with butter, and wrap the dumplings in them.

- Steam the dumplings in a steamer approx. 15 minutes at 100 deg C.

- When the dumplings are ready, remove them from the steamer, again baste with melted butter. Cut in halves, and serve. The recipe recommends cutting the dumplings with a thin string; a good sushi knife will work well too.

- YIELD: Serves 4>/li>

Slight modifications, according to the recipe, may include adding ground pepper and mace.

Serviettenknödel recipe from Vienna

Ingredients:

- 300 g (approx. 2 cups) stale white bread rolls, or white bread

- 1 medium onion or 2 shallots, chopped

- 40g (1-2 tbsp) butter

- 2 eggs

- 300 ml (1 1/4 cup) whole milk

- 1∕4 bunch flat parsley, choppedBd glatte glatte Petersilie

- Mace, freshly ground

- 1 tbsp salt

- Special tools: Large steamer and dish towel for steaming the dumpling.

Preparation:

- Wash and finely chop the parsley. Cut the bread in small cubes and place in a large bowl.

- In a saucepan, sauté the onions or shallots in butter.

- In a small bowl, whisk together the eggs, milk, and salt. Add the onions or shallots, pour over the bread cubes and mix well. Add the seasonings and taste. Add the chopped parsley, mix again and allow to rest for one hour.

- Fill a large stock pot walh way with salted water and bring to a boil. Place a 50x40 cm sheet of cling wrap (approx. 15x20 in) over a sheet of aluminum foil of the same size. Make a long roll from the dough and place it onto the cling wrap. Just like when making sushi, roll it tightly with the combined cling-wrap/aluminum/foil sheet and tighten the two opposite ends. Traditionally, it was customary to wrap the dumpling in a cotton cloth or a cloth napkin, hence the name Serviettenknödel.

- Reduce the heat to a soft boil, place the dumpling in the water, and boil for approx. 30–40 minutes. Remove and let rest for about 10 minutes

- Slice the dumpling into 2-cm thick slices (approx. 3/4 in), optionally top with melted clarified butter, and used as a side dish to goulashes, roasted beef or beef rouladen.

- YIELD: Serves 4>/li>

Serviettenknödel is called Vídeňský knedlík in the Czech Republic. There is a similar dumpling in the Czech Republic called Karlovarský knedlík (Karlsbad Dumpling), which is also made from bread, milk, flour, and eggs. The texture is very similar, with large grains of bread, encased in a small amount of flour-dough matrix. The distinction between the Karlovarský knedlík and the Vienna Serviettenknödel seems to be twofold: the original Vienna Serviettenknödel was steamed rather than boiled, and ball-shaped and served cut in halves (although one of the recipes above makes a cylindrical dumpling that is served in sliced, like Czech dumplings are). The second distinction seems to be the use of mace and parsley. The first Serviettenknödel recipe claims that the original Serviettenknödel did not use these seasonings. Our recipe for the Karlsbad Dumpling uses mace and parsley, but Zdeněk Pohlreich has a recipe on his website that omits them. The taste of the Karlsbad dumpling is further enhanced also by the whipped egg whites that are folded into the dough. This is a lesser known variant of the Czech bread dumpling and also the youngest one.

Here is an interesting recipe we like, which uses more than one kind of bread rolls to give it a multi-colored look:

|

Karlovarský houskový knedlík (Karlsbad Dumpling) |

Ingredients:

- 8 pieces of stale bread rolls (1-2 days old, kept in a plastic bag), seeds removed from the surface, cut into small pieces. Typical rolls include kaiser rolls, small baguettes etc. Rolls of various colors are desirable as they lend a nice multi-colored look to the dumpling.

- 5 eggs

- 200 g coarse flour (approx. 1 cup)

- 400-500 ml (approx. 2 cups)

- 4 tbsp fresh parsley, chopped

- 3 pinches mace

- 3 piches ground white pepper

- 8-10 pinches of salt

- Special tools: dumpling cutter

Preparation:

- Cut the bread rolls into small cubes.

- Separate the eggs yolks from the whites into to small bowls. Add the parsley, white pepper, mace, and salt to the bowl with the yolks and mix well. Add the milk and flour, and create a batter.

- In a large mixing bowl, gently mix together the bread cubes and the batter, taking care not to break up the bread cubes. Let rest for 10-15 minutes.

- In the other small bowl, beat the egg whites until firm. Fold into the dough in the large mixing bowl.

- Unlike regular bread dumplings, the Karlsbad Dupling does not have the same strength and can fall apart during boiling. Various methods are used to prevent this, the easiest one being wrapping it in a clean dish towel (or cheese cloth).

- Boil in salted water in a large stock pot for 20-25 minutes. The dumpling will float to the surface. Turn after 10 minutes to ensure it boils evenly. Pierce the casing or aluminum foil after 10 minutes to release pressure.

- To serve, slice dumplings into 1/2-inch slices using a thread or string, or a dumpling cutter.

|

Kynuté Knedlíky (Czech Raised Dumplings) |

So far, none of the Bavarian, Czech, Swabian and Tyrolean dumplings so-far used yeast. They have a dense texture and can taste a bit heavy. These raised dumplings is lighter, fluffier and more porous.

Ingredients:

- 1 lb flour

- 1/2 cup milk

- 1 tbsp salt

- 1 whole egg

- 1 egg yolk

- 1 tsp sugar

- 1/2 oz yeast

- Special tools: dumpling cutter

Preparation:

- Sift flour, ad sugar, crumbled yeast and 1/2 cup lukewarm milk. Let set until yeast bubbles up.

- Add 1 tbsp salt, egg, yolk and mix until dough is smooth. Cover and let raise in a warm place.

- With hands dusted in flour, form elongated cylindrical objects approximately 3 by 6 inches in size.

- Boil salted water in a large pot. Add the dumplings to the briskly boiling water and boil approximately 20 minutes, making sure they do not stick to the bottom or to each other. During the boiling, the dumplings will float up to the surface. Cook 10 minutes, turn over and cook another 10 minutes to ensure they cook evenly.

- Remove from the water and slice into one of them to make sure the dumplings are cooked through. Pierce dumplings with a fork to help release steam inside, if desired.

- To serve, slice dumplings into 1/2-inch slices using a thread or string, or a dumpling cutter.

|

Bramborové Knedlíky (Czech Potato Dumplings) |

Potato dumplings are a relatively late addition to Central European cuisine, dating back to late 18th century. First, their creation was condition on the introduction of potatoes to Europe from the New World. Second, they made their way to dumpling making following the poor grain harvests in 1770 and 1816.

Ingredients:

- 2 lb potatoes

- 8 tbsp farina

- 10 tbsp flour

- 1 tbsp salt

- 1 egg

- Special tools: dumpling cutter

Preparation:

- Boil potatoes, then peel and mash.

- Add farina, flour, salt and egg. Work dough well.

- With hands dusted in flour, form several 2x6-inch cylindrical dumplings.

- Boil salted water in a large pot. Add the dumplings to the briskly boiling water and cook for 20 minutes, making sure they do not stick to the bottom or to each other.

- Remove from the water and slice into one of them to make sure the dumplings are cooked through.

- To serve, slice dumplings into 1/2-inch slices using a very sharp knife, thread or string, or a dumpling cutter.

|

Špekové Knedlíky (Czech Dumplings With Smoked Bacon) |

Unlike the traditional sliced Czech dumplings, Špekové knedlíky are round balls, similar to Tiroler Speckknödel. They were most likely transplanted to modern-day Czech Republic from Tyrol during the time of the Austrian empire.

Ingredients:

- 1/3 cup smoked pork, cut into small pieces

- 1/2 cup smoked bacon, cut into small pieces

- 3 cups stale baguette, cut into pieces

- 1/2 cup flour

- 2 eggs

- 1 cup milk

- 1/4 cup lard

- 1/2 cup onions, cut into pieces

- Salt, pepper, ground nutmeg

Preparation:

- Soak the baguette pieces in milk

- Melt the lard in a sauce pan and cook the pork and onions in the lard (ouch) until onions are brown.

- Mix the baguette, milk with the onions, lard and pork in a large bowl. Add the eggs. Add salt, pepper, nutmeg, flour. Work a thick dough, adding milk or flour if needed. Cover and let rest for 10 minutes

- Boil salted water

- Divide the dough into tennis-ball size pieces and make into spheres. Cook in boiling water 25-30 minutes. Remove 1 dumpling, slice in half and test in the center. When done, remove all dumplings, slice in half and arrange on a plate.

- Serve the goulash mixture on the same plate, garnish, then drip the remaining lard over the dumplings.

|

Chlupaté Knedlíky (Czech-style Spätzle) |

Chlupaté Knedlíky translates literally as "Hairy Dumplings". They are tablespoon-size lumps of potato and flour dough boiled in salted water. They are generally similar to Spätzle, differing only in the use of potatoes (Spätzle are made of wheat flour).

Ingredients:

- 1 1/2 lb potatoes

- 1/2 lb coarse flour

- 1 egg

- Salt

Preparation:

- Peel the potatoes, grate and let drip. Save some of the liquid.

- Add salt, egg and enough flour to form a thick dough.

- Boil salted water in a large pot. Wet a tablespoon in the hot water and use it to carve out tablespoon-size pieces. Place dumplings in batches for 8-10 minutes, depending on size.

- Serve with fried bacon pieces or fried chopped onion, or as a side dish for meat roasts or smothered sauerkraut (dušené zelí).

- Alternatively, chlupaté knedlíky can be made from a mix of cooked and saw potatoes, much like Bavarian Potato Dumplings (Bayrische Kartoffelknödel).

|

Plněné Bramborové Knedlíky (Potato Dumplings Filled With Ground Smoked Pork) |

These dumplings are small balls, filled with meat. Depending on the filling that is used (i.e. pork drippings), these dumplings can be real artery-cloggers, so discretion is advised!

Ingredients:

For dumplings

- 1 1/2 lb cooked potatoes

- 1/2 lb coarse flour

- 2 eggs

- 3 1/2 tbsp vegetable oil or lard

- Salt

- 1 onion, chopped

- 1 tbsp bread crumbs

- 1 tbsp vegetable oil or lard

- 1/2 lbs pork drippings

- Salt, freshly ground pepper

- 1/2 lbs smoked pork, finely chopped or ground

- Freshly ground pepper

- 1/2 lb pork or beef, ground

- 1-2 tbsp lard

- 1 onion, chopped

- Salt, freshly ground pepper

Preparation:

- Boil potatoes a day ahead and let rest overnight.

- Grate the potatoes, add flour, salt, egg and a little oil or lard. Work into a thick dough.

- For Filling No. 1: Fry onion in lard, add the pork drippings and add bread crumbs.

- For Filling No. 2: Chop or grind the pork and season with freshly ground pepper.

- For Filling No. 3: Brown the onion in lard. Add ground meat, salt and pepper. Brown well.

- Using a rolling pin, flatten the dough into a sheet approximately 1/4 inch thick. Using a knife, divide into squares approximately 3x3 inches in size. Spoon a tablespoon-full of the filling onto each square. Using lightly flour-coated hands, fold dough and form balls.

- Boil salted water in a large pot. Boil for 10-12 minutes, depending on size.

- Serve with sauerkraut, or garnished with fried chopped onion.

Smoked pork potato dumplings with sauerkraut, topped with fried onions. |

Strawberry Dumplings in curd-cheese (tvaroh) dough |

Fruit Dumplings |

Sweet dumpling filled with fruit are a common dish in Austrian, Czech and southern German cuisine. The are and small between the size of a golf ball and an tennis ball. The dough is sweet and they are usually served topped with sugar and melted butter, but they are usually not served as a desert. They are mostly found on the menu as a main cours. Especially kids love them.

The dough could be either made of potatoes or curd cheese (quark, twarog). Quark is made by warming soured milk until the desired degree of coagulation of milk proteins is met, and then strained. It is soft, white and unaged, and usually has no salt added. The Polish word twaróg, Czech and Slovak tvaroh, the Austrian-German name Topfen (pot cheese), Flemmish plattekaas (flat cheese), the Dutch word kwark, the French fromage à la pie, are usually translated as curd cheese or cottage cheese, although curd cheese is more appropriate. This is because most commercial varieties of cottage cheese are made with rennet, whereas traditional quark is not. Quark is also distinct from ricotta because ricotta is made from scalded whey. Ricotta cheese could be substituted if absolutely desperate.

The fruit filling can be plums, apricots, strawberries, apples etc.

Jahodové knedlíky (Strawberry Dumplings). |

Ingredients:

- 1/2 lb soft curd cheese (quark, twarog), use Ricotta cheese if unavailable

- 1/2 lb hard curd cheese for grating

- 1/2 lb fresh sweet strawberries, clean and trimmed

- 1 egg

- 3/4 cup coarse flour

- 4 tbsp butter

- 1/2 cup powdered sugar

- Salt

- All-purpose flour, for the work surface

Preparation:

- Mix the soft curd, coarse flour, eggs and a dash of salt and knead into a dough.

- Divide dough into 2 halves. On a lightly floured surface, roll out into sheets no more than 1/4 inch thick.

- Cut out circles 3-4 inches in diameter. A large cup or a mixing bowl held upside down works well for that purpose.

- Place one strawberry onto each piece of dough. Seal well and form round dumplings.

- Boil in salted water for about 5-8 minutes, making sure they do not stick to the bottom of the pot. Remove and drain.

- Slice dumplings into halves. Arrange on plates, and top with melted butter, powdered sugar and grated or hard curd cheese.

Švestka (Zwetschge) from the species Prunus domestica grown in Austria and Czech Republic. |

The genus Prunus is huge. It is one of the most popular fruit trees in the world, estimated to encompass over 2000 varieties. Botanists divide it into three main categories: the European plum, the American plum, and the Sino-Japanese plum. The European plum tree has oval leaves, rather thick and dark green in color, and blooms early, in late March or early April. The fruit is oval and varies in color from blue to yellow, with a pulp that separates well from the pit. The fruit is suitable for both fresh consumption as well as drying. The plant is native to Central Asia, specifically to the area of the Caucasus. It has been cultivated in Europe since the year 1000 AD. Today, Prunus domestica is grown in Central and Southern Europe comes in several cultivars, which vary widely in sizes, shapes and colors:

- Zwetschge (Prunus domestica var. domestica)

- Kriechen-Pflaume or Hafer-Pflaume (Prunus domestica var. insititia)

- Halbzwetsche>Halbzwetsche (Prunus domestica var. intermedia)

- Edel-Pflaume>Edel-Pflaume (Prunus domestica var. italica)

- Spilling>Spilling (Prunus domestica var. pomariorum)

- Ziparte (Prunus domestica var. prisca)

- Mirabelle">Mirabelle (Prunus domestica var. syriaca)

Zwetschge-Ortenauer from Austria. |

Edel-Plaume from Austria. |

mirabelle from Austria. |

Plums from the species Prunus salicina grown in the United States. |

The Sino-Japanese plum tree has lance-shaped leaves, thin and pale green. The fruit is round and the pulp does not detach from the core and is soft and juicy. They are only suitable for fresh consumption.

In Italy, both Prunus domestica and Prunus salicina are grown. In translations of Italian recipes, the terms "plum" and "prune" are often used interchangeably, although this is incorrect. Italian chefs use the terms "European plums" and "Sino-Japanese plums" for Prunus domestica and Prunus salicina, respectively. Susina is a term used for fresh plums, while the term prugna seems to be reserved for dried fruits.

The two species of Prunus domestica and Prunus salicina have different characteristics and need to be considered when selecting ingredients for a recipe. Prugna is a fruit that can be purchased fresh in summer and autumn, but can also be eaten dried throughout the year. Dried prunes have a high concentration of sugars and minerals and caloric intake higher than those of the fresh fruit, but they contain less vitamins. Susina, on the other hand, is a fruit with a slightly acidic flavor due to a higher content of malic acid. The fruit contains a good amount of potassium and calcium, and a fair amount of vitamins. A wide variety of cultivars has been developed in Italy. They are generally intended for fresh consumption, or jams and other local dishes such as dumplings, allthough they can be dried as prunes. Some of them are:

- Early June (Prunus salicina var. Early June) - a vigorous tree that produces fruit in early summer

- Autumn Giant (Prunus salicina var. Autumn Giant) - a vigorous tree, very productive, producing very large fruit, heart-shaped, with wine-red on the surface and very waxy, with yellow flesh that is not very juicy and somewhat mediocre in flavor.

- Sorriso di primavera (Springtime Smile_ (Prunus salicina var. Sorriso di Primavera) - very vigorous plant with high and constant productivity, small to medium size fruit, spherical tending to taper the ends, with yellow-green skin with pink undertones, very waxy skin, flesh is pale yellow, not very consistent, tight, juicy, sweet, good flavor.

- Midnight Sun (Prunus salicina var. Red Beauty) - a variety introduced in 1990, of American origin, less susceptible to bacterial diseases, producing medium size fruit spherical in shape, with red and very waxy skin, yellow flesh, juicy, firm, with good flavor.

- Green Sun (Prunus salicina var. XXX) - originating in California, average to very vigorous plant characterized by high productivity, producing large spherical fruit, with skin pale green skin turning yellow and then red to bright orange, with very waxy skin, with yellow, firm flesh, with excellent qualities.

- Fortune (Prunus salicina var. Fortune) - large fruits starting intense yellow and turning bright red when ripe, round, with yellow flesh with red veins under the skin, firm, not very juicy, with medium flavor.

Most of these are grown in northern Italy mostly in Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna, and some in Piemonte. There are also some cultivars grown further south in Tuscany, Abruzzo, Campania, Liguria, even Sicily.

Autumn Giant from Lombardy. |

Sorriso di primavera from Emilia-Romagna. |

Fortune from Emilia-Romagna. |

Green Sun from Lombardy. |

Midnight Sun from Lombardy. |

Plum dumplings are found in northern Italy, Slovenia and Croatia. Because these areas were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until WWI, the rich culinary heritage of the empire extends here. They are called Gnocchi de susini. Their home base in Italy is Istria, the large peninsula in the north of the Adriatic Sea, between the cities of Trieste and Pula. It is shared by three countries: Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy. The dish is clearly the Austrian Zwetschgenknödel, but with an Italian twist. The dough is the same as that of Gnocchi di patate, but these plum Gnocchi are much larger and have a juicy plum at their heart. In addition, unlike the Czech and Austrian varieties, these are baked after having been boiled. In Istria, they can be served as a first course with a topping of melted butter and grated cheese, or as a dessert topped with sugar and cinnamon. In the average Istrian family's cuisine, there is nothing more traditional than this dish. A unique aspect of Gnocchi de susini is that it can be served as either a main course or as a dessert. Here is a recipe from Trieste.

Gnocchi de susini Italian Plum Gnocchi From Potato Dough

Ingredients:

- 2.2 lbs potatoes

- 12-15 plums - read the above discussion of vast variety of Italian plum cultivars, but for this dish, "Italian Prunes" are used. These are dark blue plums resembling the Austrian Zwetschgen

- 1 cup (approx. 200 g) fine-grained flour (Italian Tipo 00, same as would be used for pizza crust)

- 1 tbsp (30 g) butter

- 1 tbsp cinnamon

- 1 tbsp caster sugar

- YIELD: Serves 4

Preparation:

- Boil the potatoes until tender, but not too soft, else they absorb too much water and make the dough too sticky. Let cool enough to handle. Peel and mash the potatoes and allow to cool for at least 20 minutes.

- Add the sifted flour and mix until homogeneous, slightly sticky mixture is obtained.

- Wash the plums, cut them in half and remove the pits. Fill the cavity left by the pit with a tsp of sugar and recompose the plums.

- Cut the dough into golf ball sized portions, flatten them with your hands or with a rolling pin, place a plum in the middle and wrap the dough around it. Make sure the dough is sealed well, otherwise the juice will spill out during cooking.

- Fill a large pot with water, add a tbsp of salt, and bring to a boil. Boil the gnocchi, in batches to prevent sticking, for 10-15 minutes. They will float to the surface when finished.

- In the meantime heat the oven to 350 deg F (180 deg C). Melt the butter and use some to grease a deep baking sheet or a skillet. Remove the gnocchi from the pot using a slotted spoon, and place them on the baking sheet. Sprinkle with sugar and abundant cinnamon, then pour the melted butter on top. Place the pan in the oven and cook the Gnocchi for 15 min. Pour the sugary butter on top of the Gnocchi and sprinkle with some additional sugar. Serve hot.

Moving north, Austrian and Czech plum dumplings are boiled, never baked like the Italian ones, and use locally available plums belonging to the species Prunus domestica. Two types of dough can be used: either potato dough as in the Italian version, or lighter dough made of curd cheese.

Zwetschgenknödel (Plum Dumplings). |

Ingredients:

- 2-3 medium russet potatoes

- 1 egg, beaten

- 1/4-1 cup all-purpose flour

- Pinch of salt

- 12 plums, pitted (this being Austria, dark blue Zwetschgen from the species Prunus domestica would normally be used

- 1 cup plain breadcrumbs

- 3 tbsp unsalted butter

- granulated sugar

- ground cinnamon

- YIELD: Serves 4-6

Preparation:

- Boil the potatoes in the skin. Let cool enough to be handled, peel. then let cool completely. Potatoes can be cooked a day ahead of time; the dough will stick together better.

- Finely grate the cold potatoes. Add the egg, pich of salt and the flour. The amount of flour may differ, depending on how moist the potatoes are. The goal is to obtain a dough that stick together nicely, yet can be rolled out and formed easily.

- Form the dumplings. For each dumpling, take a piece of dough about the size of a golf ball. Roll it gently in your palms to form a rough ball. Then use your thumb to create a deep indentation in the center of the ball. Place a plum in that indentation and use your fingers to mold the dough around the plum. Be sure to completely envelope the plum in dough.

- Bring a large pot of water to boil. Gently drop the dumplings into the water, making sure that they do not stick together. Boil over high heat, until the dumplings all float to the top, about 15 minutes. Remove the dumplings with a slotted spoon.

- While the dumplings are boiling, melt the butter in a saucepan over low-medium heat. Add the breadcrumbs and cook, stirring, until the breadcrumbs are golden and fragrant.

- To serve, split the dumplings and top with plenty of breadcrumbs. Sprinkle with sugar and cinnamon to taste.

Next is a Czech recipe, generally similar to the Austrian one except it omits the breadcrumbs, and uses a topping of sour cream and ground poppy seeds.

Švestkové knedlíky (Plum Dumplings). |

Ingredients:

- 1 lb potatoes

- 2 eggs

- 1/2 lb semi-coarse flour

- Pinch salt

- 1 lb plums (dark blue švestky from the species Prunus domestica would normally be used)

- 1 cup sour cream

- 70 g (3-4 tbsp) rozpuštěného másla

- Ground poppy seeds and confectioner's sugar, for garnish

- YIELD: Serves 4

Preparation:

- Boil the potatoes in the skin. Let cool enough to be handled, peel. then let cool completely. Potatoes can be cooked a day ahead of time; the dough will stick together better.

- Finely grate the cold potatoes. Add the 2 eggs, pich of salt and the flour. The amount of flour may differ, depending on how moist the potatoes are. The goal is to obtain a dough that stick together nicely, yet can be rolled out and formed easily.

- Clean the plums. The can be pitted or left whole, based on your preference. Pitted plums will release juice during boiling. In that case, prepare the dough a bit thicker.

- Boil water in a large pot. Roll out the dough to about 1/2 cm thickness (1/5 in). Divide into palm-size pieces, place a plum onto each of them, and form round dumplings. Carefully place the dumplings in boiling water and boil, covered, approximately 5 minutes. When they are finished, they will float to the surface. Boiling the dumplings covered gives them a fluffy character.

- While the dumplings are boiling, in a bowl, mix the sour cream with the ground poppy seeds and confectioner's sugar.