|

History of Créole Food

... with a bit of Louisiana history thrown in ...

Introduction

New Orleans has a unique cuisine, but not too many really understand how it evolved.

Non-Louisianians often think that New Orleans cuisine, Créole food and Cajun food are the same thing,

which they are not. Moreover, the terms "Créole" and "Cajun" are often misunderstood and confused,

not only when it comes to cuisine.

The New Orleans cuisine of today is a blend of several things: the 18th century Créole cooking,

itself based on French, colonial, African and Native American recipes and ingredients;

Cajun, the country-food of Acadian refugees who settled in Louisiana in the second half of the 18th century;

Soul Food; and additional Italian and Spanish influences brought in by later 19th century immigrants.

While some recipes are common to both Créole and Cajun cuisine, such as gumbo and jambalaya, there are many

that are typical of each. Louisiana Créole cuisine tended toward classical European styles

adapted to local resources. Broadly speaking, the French influence in Cajun cuisine descended

from various French Provincial cuisines of the peasantry, while Créole cuisine evolved in

the homes of well-to-do aristocrats, or those who imitated their lifestyle.

Oysters en brochette. |

Some of the typical Louisiana Créole recipes include crabmeat ravigote, oysters en brochette,

shrimp remoulade, crawfish bisque, oyster and artichoke bisque,

shrimp Créole, trout à la meunière, shrimp bisque, bananas foster, New Orleans bread pudding,

doberge cake, pralines, pecan pie, café brûlot, café au lait, eggs sardou, grillades and grits...

Typical Cajun food. |

Compare it to some typical Cajun recipes, which inlude boudin sausage, gumbo des herbes, crawfish étouffée,

couche couche, boiled crawfish, maque choux, tasso, catfish or redfish court-boullion, hog's head cheese,

various types of sauce piquante (Shrimp, Alligator, Turtle), cochon de lait (roasted suckling pig), crawfish pie,

andouille sausage, dirty rice, rice and gravy, fried frog legs, tarte à la bouillie

(sweet-dough custard tarts), seafood-stuffed mirliton, brochette... Although the names sound French, this

is not French cuisine either; most of these recipes do not exist in France today.

Where is the difference? And, more importantly, why? This essay attempts to explain that

against the background of the history of Louisiana. Lousiana history is a centuries-long epic struggle

for land, wealth and power by some of the world's greatest nations. Set against the backdrop of our favorite subject, food,

Louisiana history and cuisine are unique simply because Louisiana is not historically Anglo-Saxon American,

but French and Spanish in origin. Louisiana developed through a completely different avenue, compared to its neighbors,

Texas and the traditional South.

Viceroyalty of New France

The history of Créole cuisine in Louisiana begins around the time of the first French settlement

De Soto Discovers the Mississippi

by Currier and Ives, 1876 |

established in 1682. However, to be precise, the Spanish were in the Gulf of Mexico first (Ponce de Leon in 1513,

Alvarez de Pineda in 1519, Panfilo de Narvaez 1528, Hernando de Soto from 1539 to 1543).

It was de Soto who finally reached the Mississippi River. Having failed to discover gold

(the metal, not black gold), they left and it was not until more than a century later

that a more or less permanent settlement stuck.

French explorers, in search of resources, trade and the fabled Sea of China,

first came to North America in the 16th century. They explored its eastern coast

from Florida to Newfoundland, including the St. Lawrence River.

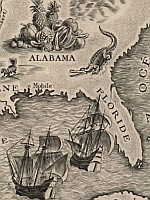

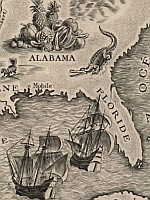

Click to enlarge |

These efforts led to the establishment of Vice-royauté de Nouvelle-France

(Viceroyalty of New France), which became a major colony in 17th and 18th century

North America. To imagine how large it was, one has to take into account

that, at its peak, it covered most of North America and was at least as large as

the United States are today. With the capital in Quebec, Nouvelle-France stretched

north-south from Hudson Bay to the mouth of the Mississippi River, and

east-west from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River through the Ohio Valley

to the Rocky Mountains. New France also effectively barred

the westward expansion of the thirteen English colonies. It is obvious from the map

that much of North America belonged to France at that time!

Census shows that the population of Nouvelle-France was about 3215 people 1666, and 90000

a century later. The colonists who inhabited Canada came mainly from Paris, Île-de-France

and the provinces of Aunis, Brittany, Normandy, Picardy, Poitou and Saintonge.

Those who settled Acadia were mainly from the provinces of Anjou, Maine and Touraine.

Newfoundland was founded by the Basques in southwestern France.

Louisiana, which was colonized last, was mainly populated by settlers already

established elsewhere in Nouvelle-France.

Cities of Quebec, Montreal, Detroit, Green Bay, Saint Louis, Mobile, Biloxi, Baton Rouge,

New Orleans, Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haïtien owe their origin to

the Vice-royauté de Nouvelle-France.

In the 17th century, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French minister of finance under King Louis XIV,

and Cardinal Richelieu (Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu, Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu),

were the main agents of colonial policy in the Council of the King of France.

Mercantilism inspired the decisions taken to Nouvelle-France, whose development

was entrusted to the government and charter companies formed by investors

for the purpose of trade, exploration and colonization. In 1663 the Conseil

souverain de la Nouvelle-France (Sovereign Council of New France) was created

outside the royal domain to take over from the colonial companies.

Throughout the 17th century, explorers such as Jean Nicolet, Louis Joliet,

Jacques Marquette, Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, and one René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

continued their exploration to the Great Lakes and then south. They discovered Green Bay

west of Lake Michigan, and explored the Missouri, Ohio, Illinois and Mississippi Rivers.

Of particular importance to Louisiana history are the explorations of the Ohio, Illinois

and Mississippi Rivers by de La Salle undertaken in 1669-1670.

In the 17th century, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French minister of finance under King Louis XIV,

and Cardinal Richelieu (Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu, Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu),

were the main agents of colonial policy in the Council of the King of France.

Mercantilism inspired the decisions taken to Nouvelle-France, whose development

was entrusted to the government and charter companies formed by investors

for the purpose of trade, exploration and colonization. In 1663 the Conseil

souverain de la Nouvelle-France (Sovereign Council of New France) was created

outside the royal domain to take over from the colonial companies.

Throughout the 17th century, explorers such as Jean Nicolet, Louis Joliet,

Jacques Marquette, Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, and one René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

continued their exploration to the Great Lakes and then south. They discovered Green Bay

west of Lake Michigan, and explored the Missouri, Ohio, Illinois and Mississippi Rivers.

Of particular importance to Louisiana history are the explorations of the Ohio, Illinois

and Mississippi Rivers by de La Salle undertaken in 1669-1670.

Cavelier de La Salle

by Pierre Gandon, 1937 |

In 1666 a 23-year-old adventurer and ex-Jesuit student named René-Robert Cavelier from Rouen

in northern France, came to Canada. Cavelier was granted a seigneurie (landlordship)

on land at the western end of the Island of Montreal. (Seigneurie was a system of

semi-feudal land distribution introduced in Nouvelle-France by none other than

Cardinal Richelieu.) Cavelier, now René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, learned from

the Mohawk of a great river, the Ohio, which flowed into another great river, the Mississippi.

That river obviously flowed into a sea, which could provide a western passage to China,

which is what he was ultimately after. In 1669 he led his first expedition down the

Ohio River and reached as far south as present-day Louisville, Kentucky.

Between 1680-1682, de La Salle and one Henri de Tonti, an Italian-born soldier, explorer,

and trader in the service of France, tried to colonize the Illinois River with varying success.

In 1682, de La Salle, de Tonti and 18 Native Americans canoed down the Mississippi River.

The Natives taught them that the river was navigable and that it flowed into the sea at a place

near the Spanish colonies. As they continued their exploration down the river, the climate gradually

became warmer with alligators inhabiting the waters, the river banks became low and swampy,

the river water brackish. They reached the end of the Mississippi delta on April 9, 1682, near

the present-day port and oil-industry logistics base at Venice, Louisiana. De La Salle

erected a cross and

The Natives taught them that the river was navigable and that it flowed into the sea at a place

near the Spanish colonies. As they continued their exploration down the river, the climate gradually

became warmer with alligators inhabiting the waters, the river banks became low and swampy,

the river water brackish. They reached the end of the Mississippi delta on April 9, 1682, near

the present-day port and oil-industry logistics base at Venice, Louisiana. De La Salle

erected a cross and

"Taking Possession of Louisiana and the River

Mississippi, in the name of Louis the XIV,

by Cavelier de la Salle

on the 9th of April, 1682"

by Jean Adolph Bocquin, c. 1850 |

buried an engraved plate, and proclaimed the whole Mississippi Basin for France. He named it Louisiana,

to honor King Louis XIV, le Roi Soleil (the Sun King), the ruler of France at the time.

In doing so, de la Salle managed to acquire for France the most fertile half of the North American continent.

The entire region from the mouth of the Mississippi River to Canada became known as la Louisiane.

French Louisiana

La Louisiane joined the other colonies comprising Vice-royauté de Nouvelle-France:

l'Acadie and Canada. The colony of Canada (or New France) was formed in 1534,

and served as the cornerstone of the French colonial empire in North America until 1763.

The colony consisted of three districts: Québec, Montréal and Trois-Rivières.

The governor of Quebec was also the governor-general of all of New France.

The terms "Canada" and "New France" were often used interchangeably. Dependent on the

colony of Canada were the Pays d'en Haute (Upper Country, all of Great Lakes region

and as far west as the French had explored) and Pays des Illinois

(Illinois Country, present-day Mid-western U.S. states).

Canada was ceeded to Britain in 1763 under the Treaty of Paris, following the

French loss of the Seven Years' War.

La Louisiane joined the other colonies comprising Vice-royauté de Nouvelle-France:

l'Acadie and Canada. The colony of Canada (or New France) was formed in 1534,

and served as the cornerstone of the French colonial empire in North America until 1763.

The colony consisted of three districts: Québec, Montréal and Trois-Rivières.

The governor of Quebec was also the governor-general of all of New France.

The terms "Canada" and "New France" were often used interchangeably. Dependent on the

colony of Canada were the Pays d'en Haute (Upper Country, all of Great Lakes region

and as far west as the French had explored) and Pays des Illinois

(Illinois Country, present-day Mid-western U.S. states).

Canada was ceeded to Britain in 1763 under the Treaty of Paris, following the

French loss of the Seven Years' War.

The other colony, Acadie (Acadia), was formed in 1604 and was part of

New France until 1713 when it was ceeded to Britain under the Treaty of Utrecht.

Located in the northeast corner of North America, it included New Brunswick, Nova Scotia,

Isle St-Jean (Prince Edward Island), and parts of present-day Maine.

Beside Acadia, under the Treaty of Utrecht, France also ceded to Great Britain its claims

to Terre Neuve (Newfoundland) and to the Hudson's Bay Company territories in Rupert's Land.

The formerly partitioned island of Saint Kitts was also ceded in its entirety to Britain.

France was required to recognise British suzerainty over the Iroquois and commerce with the

Far Indians was to be open to traders of all nations.

France retained its other pre-war North American possessions,

including Île-Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island), Saint Pierre and Miquelon,

as well as Île Royale (Cape Breton Island).

The Natives from the Dakota, Ojibwa, Iroquois, Natchez, Houma and other nations

obviously received the proverbial short end of the stick.

Before 1713, the total territory France controlled in North America extended from

Newfoundland to the Rocky Mountains and from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico!

When La Louisiane was added to the French colonial empire in North America,

De La Salle returned to France to receive a warm welcome from Louis XIV.

In 1685, he sailed back to America with 4 of the king's ships to continue his colonial ventures

in the Mississippi Valley. However, his second expedition ended in a complete failure.

After losing 3 ships in the Atlantic and in the Gulf of Mexico, his sailors defecting to pirates,

missing the mouth of the Mississippi River, looking for it along the coast all the way to Mexico,

When La Louisiane was added to the French colonial empire in North America,

De La Salle returned to France to receive a warm welcome from Louis XIV.

In 1685, he sailed back to America with 4 of the king's ships to continue his colonial ventures

in the Mississippi Valley. However, his second expedition ended in a complete failure.

After losing 3 ships in the Atlantic and in the Gulf of Mexico, his sailors defecting to pirates,

missing the mouth of the Mississippi River, looking for it along the coast all the way to Mexico,

Click to enlarge |

building a temporary settlement near Matagorda Bay, searching for the Mississippi on foot,

finally finding it by chance, de La Salle was killed by two of his men in 1686.

Out of the original 300 colonists, at this point only 36 remained.

The settlement near Matagorda Bay lasted until 1688, when the Natives killed the 20 remaining adults

and took five children as captives. De la Salle's exploits came to an end.

de Bienville by Rudolf Bohunek, 1908 |

After the failure of the de La Salle expedition, the exploration of Louisiana was interrupted for 12 years.

In 1697, the Montreal-born Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville was chosen by Louis Phélypeaux, count of Pontchartrain,

the Secrétaire d'État de la Marine, to re-establish a colony in Louisiana. He left France in autumn 1698

with a fleet of five ships. D'Iberville did find the Mississippi and founded the first capital of the colony: Biloxi

and later Mobile. In 1703, after his last trip to Louisiana, d'Iberville left in charge of the colony his younger brother

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, and went to fight the British in the West Indies, where he died in 1706.

Louisiana struggled as a royal colony from 1699 to 1712. War broke out between France and Britain

in 1701 (War of the Spanish Succession) and lasted until 1714. The colony was cut off from France for years at a time.

The population remained quite small. By 1712 the French monarchy was becoming financially-challenged.

Banker Antoine Crozat proposed to the King the creation of a charter company that would have a total monopoly for trading in Louisiana.

In September 1712, Crozat obtained that privilege for fifteen years and gained control of Louisiana.

In 1717 the slow-growing colony came under the control of the Compagnie d’Occident (Company of the West),

headed by Scottish financier John Law.

New Orleans

de Bienville by Rudolf Bohunek, 1910 |

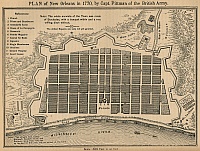

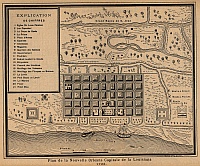

In 1718, under the direction of de Bienville, the Compagnie d’Occident founded the city of

La Nouvelle-Orléans to serve as the new trading post. The city was named for Philippe d'Orléans, Duke of Orléans,

who was the Regent of France at the time and whose title came from the city of Orléans in north-central France.

The site was selected because it was a relatively high ground on the natural levee created by the sedimentary

processes of the Mississippi River, and beause it was adjacent to the trading route

and portage between the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain via Bayou St. John. From its founding,

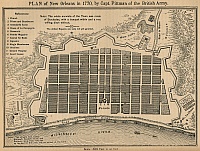

New Orleans in 1728 (click to enlarge). |

the French intended it to be an important colonial city. The Jesuits and the Capuchins came in 1722,

followed by the Ursuline Sisters in 1727. In 1722, Nouvelle-Orléans was made the capital

of la Louisiane, replacing Biloxi in that role.

Because the bank invested heavily in the Compagnie d’Occident and, because Louisiana was the company’s

greatest asset, the colony needed rapid development to maintain public confidence in the bank.

A promotional campaign was undertaken that brought in several thousand settlers.

The settlers also included convicts who were forced to migrate to the colony.

According to one company official, 7020 Europeans arrived in the colony between October 1717 and May 1721.

After Law’s company had acquired the Compagnie du Senegal, which held the French monopoly on the slave trade,

black slaves from Africa were brought to Louisiana in 1719. About 3,000 slaves arrived between 1720 and 1731.

The Compagnie d’Occident aimed for an accelerated commercial development of the colony, but

things were definitely not glitz and glamor in New Orleans during this time. In September 1722, a hurricane struck the city,

blowing most of the structures down. A good deal of the population was of the wildest and the most undesirable character:

deported galley slaves, trappers, gold-hunters and urban riffraff. Law’s promotional literature led immigrants

to anticipate quick profits from mining and other endeavors. However, the harsh world they found was dramatically different.

Many people died because the overwhelmed colonial government could not meet their needs for food, clothing, and shelter.

Most of the survivors stayed simply because they lacked the means to return to Europe.

Although a few large plantations were established, most of the immigrants tilled small subsistence farms,

sometimes with slave labor. These farmers engaged in small-scale production of tobacco and indigo for export.

Foundations of the Louisiana Créole Culture

It is nevertheless during this period that the foundation of the Louisiana Créole society was laid down.

To understand New Orleans, it is important to realize that it is not the traditional "South" and

its history did not look like in "Gone With The Wind".

Laura Plantation |

La Louisiane was part of Le Monde Créole,

the Créole World, a French/Spanish-controlled or -influenced

part of the world stretching from Brazil through the Caribbean to Louisiana.

The Créole culture of New-Orleans was part of Créole cultures world-wide, including Cuba, Haiti,

Guadeloupe, Martinique and the entire Caribbean, or even places like Mauritius, Reunion,

the Seychelles or Portuguese Goa in the Indian Ocean, and the Guianas and Brazil in South America.

Indeed, the roots of Louisiana and New Orleans lie there rather than in Anglo-Saxon North America.

All of Le Monde Créole shares similar histories of colonial liberalism,

the same ethnic roots, architecture, music, folklore, life-styles, family and business values.

New-Orleans is only one small part of Le Monde Créole.

Today, in Louisiana, "Créole" generally means a mixed-race person or people of African-American, French or Spanish descent,

traditionally Catholic, with origins in New Orleans.

However, before the Civil War, the term Créole was used to describe those colonists of French and Spanish descent

born in la Louisiane, possibly with some African or Native American blood mixed in.

The term was used to differentiate thos born in the colony from those born in France.

French Quarter patio. |

The Créole society was a class system, not a race system. It was based on family ties, position, wealth, and connections.

It was more elitist than it was democratic. Most of the modern European thought of the 18th century Enlightment

(Le Siécle des Lumières) did not make it into Créole philosophy, economics and politics.

Nostalgia aside - life was tough. The difficult lessons of survival during the first years in frontier Louisiana

forged a very family-centered, conservative view of the world. A strict, self-serving pragmatism

was followed, formed out of isolation and desesperation that characterized Louisiana in its early years.

Créole Woman by Edouard Marquis, 1867. |

The Créole society developed a 3-tier mixed-race class system: white business owners of French and Spanish origin,

gens de couleur libres (free people of color), and slaves. Parisian French was the language spoken.

As European women tended to be in short supply, men started interracial marriages with enslaved or free

black- or mixed-race women, resulting in a mixed mulatto progeny. These become gens de couleur libres,

free people of color. These mixed-race Créoles rapidly began to acquire education, skills, businesses and property.

They were overwhelmingly Catholic, spoke mainly Colonial French and kept up many French social customs,

modified by other parts of their ancestry and Louisiana culture.

The French-speaking mixed-race population came to be called "Créoles of color".

Carriageway in a French Quarter

townhouse. |

The Créole high society, whites as well as Créoles of color, consisted of plantation owners, bankers, traders, etc.

Young men were given mistresses who were black or mulatto, but they couldn’t marry them. Having a mistress

was an accepted custom because marriages were usually business arrangements, and having a mistress was facilitated

by the plaçage system, a recognized extralegal system in which white French and Spanish and later Créole men entered

into the equivalent of common-law marriages with women of African, Indian and white (European) Créole descent.

Some placées, such as Rosette Rochon, even became entrepreneur, bankers and speculators.

Men took lessons in fencing, horseback riding, and dancing. Girls had to marry before they were twenty-five years old.

They usually had a "coming out" during an evening at the Theatre d’Orleans, which marked the beginning of their

search for a husband. An elaborate sequence of courtship and business deals between the two families

(and their lawyers and notaries) followed. A few days before the wedding, the young man gave his fiancée

a wedding basket with lacework (handkerchiefs, mantilla, fan), a cashmere shawl, gloves, and jewelry. She

The Family of Dr. Joseph Montegut

by Jose de Salazar, c. 1790 |

could not wear the jewelry before the wedding, nor could she leave the house for three

days before the wedding. The Créoles liked to have weddings on Mondays or Tuesdays in Saint Louis Cathedral

in New Orleans in the late afternoon. Religious customs focused on holidays: All Saints Day,

Mardi Gras, Easter and Christmas. On All Saints Day, Créoles brought paper flowers to place on

graves in the cemetery. Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday) was celebrated on the Tuesday before Ash

Wednesday, the beginning of Lent. This celebration descended from the Catholic carnival traditions

of Rio de Janeiro, the carnival in Venice, the Czech Masopust and the German and Austrian Fasching.

Revellion dinner. |

At Christmas, the Créoles celebrated the Reveillon (awakening).

Families assembled on Christmas Eve, went to Midnight Mass at the Saint Louis Cathedral together,

then broke the daylong religious fast with a large meal when they returned home.

They would have an elaborate meal consisting of chicken and oyster gumbo, game pies, soups,

soufflé, lavish desserts, brandy and coffee, going on through the early morning.

The second Reveillon came on New Year's Eve, and was even more festive and sumptuous.

When the French started arriving in la Louisiane, they brough with them

classic Parisian cuisine, or at least memories of it. What they found was en environment rich in seafood,

but with spices and ingredients, some of which were quite different from those used in Parisian cuisine.

Créole cuisine became refined and sophisticated, but it was not the same as Parisian cuisine any more.

Shrimp remoulade. |

While some of the sophisticated sauces such as rémoulade made it into Créole cuisine, some typically

New Orleans dishes such as crawfish bisque would not be found on the menu in

a restaurant in Paris. Créole cuisine became city cooking, based on French stews and soups, but with

influences from African and Spanish cuisines. The Spanish brought into the cuisine the use of cooked onions,

green peppers, tomatoes, and garlic. African chefs brought with them the skill of spices and introduced okra.

>From the Choctaw Indians came the use of filé, a powdered herb from sassafras leaves, to thicken gumbo.

The Italian dimension apparent in Créole cuisine today was added later, in the late 19th and

early 20th century.

Today, the cuisine of New Orleans is undeniably butter-rich. Nearly every dish from apperizer through

main course to dessert will be surrounded by melted butter. If the word "sautéed" appears on a menu,

the words "in butter" will not be far behind.

It is important to realize that Cajun cuisine did not originate until the second half of the 18th century,

after the arrival of Acadian exiles expelled from colonies in Canada following the Seven Years' War.

Such was Le Monde Créole, the Créole World: not necessarily democratic, not necessarily safe, or fair

to everyone, but certainly colorful and and full of traditions most of which have disappeared today.

Compared to the Anglo-Saxon America of the time, the Créole society did offer more social mobility

to those blacks who were gens de couleur libres, as well as more roles to women as business owners.

An excellent introduction into the Créole history of Louisiana is given by

a tour company in New Orleans called "Le Monde Créole". The tour consists of 2 parts:

a guided tour of the Laura Plantation, an hour north of New Orleans on River Road by car,

followed by a guided tour of several town houses in the French Quarter. Rather than a routie

account of dates and where this sofa and that painting came from, Le Monde Créole focuses on

re-creating an image of Créole life using the example of a particular wealthy plantation family.

This is based on the diary of Laura Locoul, a Créole woman and plantation mistress, who

wrote a journal of her family's life in 18th century New Orleans.

The Seven Years' War And the End Of

Viceroyalty of New France

In 1756, the Seven Years' War broke out in Europe, known in North America as the French and Indian War

or The War of Conquest. It was a major military conflict that involved all of the European powers of the time.

It spread globally and effectively became the first "World War". The war pitted Prussia, Britain, Portugal

and a coalition of smaller German states against France, Austria, Spain, Russia, Sweden, and Saxony.

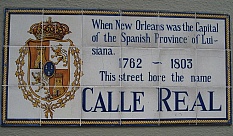

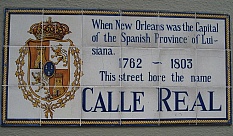

In 1762, seeing that things were not going well, France ceded la Louisiane française to Spain

in a secret agreement called The Treaty of Fontainebleau, to induce Spain to enter the war as a French ally.

However, the following year the French and Spanish lost the war, and in the peace treaty Britain took

nearly all of Louisiana east of the Mississippi. Spain kept the larger western part, along with the Ile d’Orléans

(the area around New Orleans), which retained the name Louisiana. The British Empire effectively emerged

|

from the war as the victor, having strengthened its colonial position through the 1763 Treaty of Paris,

and confirming its status as the globally dominant colonial power. This was the end of the

Vice-royauté de Nouvelle-France, the French colony of North America.

The city of La Nouvelle-Orléans became Spanish.

Spanish-era wrought-iron architecture. |

Ursuline Convent. |

Nearly all of the surviving 18th century architecture of the French Quarter dates from this Spanish period.

The Old Ursuline Convent is the most notable exception.

Origins Of the Cajuns

The Treaty of Paris had another profound effect: it was the driving force behind the second wave

of French-speaking immigration into Louisiana. Acadie was one of the divisions

of Nouvelle-France, and included parts of eastern Québec, the Maritime provinces of

New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, and parts of modern-day New England.

Following the end of the war, the British took over Acadie and the expelled

its Catholic, French-speaking population. The Acadians started to migrate to the

closest French-ruled and French-speaking colonies. Many migrated to Saint-Domingue (Haiti)

and others continued to Louisiana. Only after many Acadians had moved to Louisiana,

seeking to live under a French government, did they discover that Louisiana was Spanish!

(The formal announcement of the transfer was not made until made in December 1764.)

The Acadians took part in the Rebellion of 1768 in an attempt to prevent the transfer, but Spain formally asserted control in 1769.

The Spanish governor Bernardo de Gálvez later proved to be hospitable and permitted the Acadians to continue to speak

their language and practice Catholicismn. Later, Acadians also fought in the American Revolution

(although for the Spanish General Galvez because "the enemy of my enemy is my friend".). The Acadians' joining

the fight against the British was partially a reaction to the British having evicted them from Acadia.

Acadiana (Cajun country). |

The Acadian exiles settled along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, in the present-day

southwest part of Louisiana. This area became known as Acadiana (L'Acadiane in Cajun French), or simply

as "Cajun Country". It is important to realize that the Acadian exiles, although they spoke French,

had historicaly nothing to do with the Créoles. This is the cornerstone of the distinctions between the two

French-speeaking cultures of Louisiana. The Créoles were earlier descendants of French and Spanish settlers,

born in the colonies and often mixed with Black and Native blood, living in New Orleans and its environs,

making a living as tradespeople, merchants, businessmen and plantation owners.

On the other hand, the Acadians were rural folks who settled the coastal areas of southwest Louisiana, and

became later known as "Cajuns". Both groups had distinct dialects, customs and culture, including cuisine.

Modern-day Cajuns descend not only from these Acadian exiles who settled in south Louisiana in the eighteenth century,

but also from intermarriages with other groups: British, Spanish, German, Italian, Native American, Métis and

French Créole settlers. Although Cajuns today are portrayed as cozy, mellow country folks, not everything

has gone smoothly for them. Every society tends to create nostalgia for an idealized version of the past.

During the early part of the 20th century, attempts were made to suppress Cajun culture by measures such

as forbidding the use of the Cajun French language in schools. "Cajun" was formerly considered an insulting term.

In 1968 the organization of Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) was founded to preserve

the French language in Louisiana.

Pot of Jambalaya. |

The cuisine of the Cajun Country is peasant food. Often mistakenly attributed to New Orleans,

Cajun cuisine has its roots with the rural settlers from Acadia, not Parisian aristocrats. The Acadians

brought their frontier cuisine and adapted it to the then-remote areas of Acadiana.

The cuisine is rustic, flavorful and bold, as opposed to Créole food, which is more refined and subtle.

Cajun food is pungent and more highly spiced. Long-simmering one-pot dishes such as crawfish étouffée,

shrimp jambalaya, gumbo with roux reflect their survival-oriented traditions.

Louisiana Purchase And "Les Américains"

Battle at San Domingo

by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres,

1803-1804. |

In 1800, Napoléon Bonaparte, then the First Consul of the French Republic, regained part of the

original Louisina territory from Spain through a treaty called the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso.

This was a secretly negotiated deal between the French Republic and the Kingdom of Spain,

signed at the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso near Madrid, under which the French Republic would establish

a newly created territory on the Italian Peninsula on behalf of the prince Louis Francis of Bourbon-Parma,

and Spain would retrocede the colony of Louisiana to France. The treaty was kept secret and Louisiana remained

under Spanish control until 3 years later, just three weeks before the Louisiana Purchase by the United States.

Battle at San Domingo

by January Suchodolski, c. 1875. |

In 1803, France had just experienced a costly slave revolution in Saint-Domingue (Haiti). The French army was

unable to spress it, leading Napoléon to abandon his plan to rebuild his colonial empire in North America

and make Saint-Domingue the keystone of it. Without revenues from other colonies in the Caribbean,

Louisiana by itself had little value to him. In addition, in 1803 the first in a series of Napoleonic wars was about to break out.

The impending war with Britain meant that money would be needed to wage it. It also made him question the feasibility

of holding Louisiana against Britain, the greatest naval power of the time. In the end, it was decided to

liquidate Louisiana and sell it to the United States.

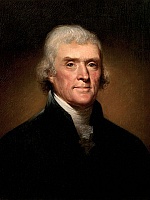

Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale,

1800. |

President Thomas Jefferson initiated the purchase by sending Robert R. Livingston to Paris in 1801,

having discovered the transfer of Louisiana from Spain to France under the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso.

Livingston was authorized to purchase New Orleans. in 1803, James Monroe and Livingston traveled to Paris

to negotiate the purchase but their interest was only in the port and its environs. They did not

anticipate the much larger transfer of territory that would follow! On April 11, 1803,

The French Treasury Minister François de Barbé-Marbois offered Livingston all of Louisiana

at a price of $15 million.

The Americans were prepared to pay up to $10 million

for New Orleans but were surprised when the vast Louisiana territory was offered for $15 million.

The transaction nevertheless happened and, on a per-acre basis, the United States bought the land for 3 cents per acre, more than doubling its territory overnight.

The Americans were prepared to pay up to $10 million

for New Orleans but were surprised when the vast Louisiana territory was offered for $15 million.

The transaction nevertheless happened and, on a per-acre basis, the United States bought the land for 3 cents per acre, more than doubling its territory overnight.

Canal Street in the 1850s. |

The transfer of the French colony to the United States and the arrival of Americans from New England and the South

ignited an outright cultural war. Some Americans were shocked by the Créole culture:

the dominance of French and Catholicism, the free people of color, and the the strong African traditions.

In turn, upper-class Créoles saw many of the arriving Americans as lacking good manners, refinement

and sophistication, and referred to them disdainfully as les Américains.

Créoles of both white ancestry and free people of color resisted American attempts

to impose a culture splitting the population into black and white, because they were used to

having one fluid upper class of mixed-race people. New Orleans became a city divided between Latin

(Spanish, and French Créole) and American populations, which until the late 19th century.

The Créoles lived east of Canal Street, while the newly arriving Americans settled west of it.

Canal Street became the dividing line. To this day, a Neworleanian will not refer to the grassy median

in the middle of a boulevard as a "median" but as "neutral ground", which is a slang derived from that era.

Oak Alley plantation. |

It is also important to realize that the stereotypical - mainly Hollywood-bred - view of Antebellum New Orleans,

of Garden District mansions with colums with lawns and wrought-iron fences, and of plantations with oak

trees and white columns, is the newly developing American New Orleans, not the Créole New Orleans.

The 19th Century

The United States split the Louisiana Purchase into two parts: the District of Louisiana

(renamed Territory of Louisiana in 1805) north of the 33rd parallel

(the northern border of present-day Louisiana), and the Territory of Orleans to the south.

William C. C. Claiborne became governor of the Territory of Orleans.

In 1809 numerous refugees from Saint-Domingue (Haiti) arrived in New Orleans, doubling its population.

In 1810 American settlers in West Florida proclaimed their independence from Spain

and requested annexation by the United States. Claiborne assumed control over a portion

of that that region, up to the Pearl River. On April 30, 1812, the Territory of Orleans

entered the federal Union as the 18th state, the State of Louisiana.

It included the annexed part of West Florida. Claiborne became the first state governor

and New Orleans continued as the capital.

In 1818, the United States ceded a portion of the Louisiana Purchase to the Great Britain,

in a setttlement following the War of 1812. In that treaty, the United States ceded to Great Britain

that portion of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 49th parallel in present-day Alberta and Saskatchewan,

in exchange for other British posessions south of the 49th parallel.

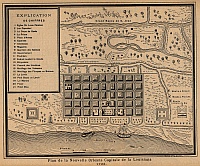

New Orleans in 1770 (Click to enlarge). |

19th century New Orleans grew rapidly and the region became quite wealthy.

Between 1830 and 1860 it became the second largest port of entry for immigrants after New York City.

During that time, over 550,000 immigrants came to New Orleans. By 1850 about one-quarter

of the population of Louisiana and the majority of

the white population of New Orleans was foreign-born.

New Orleans in 1863 (Click to enlarge). |

The old Créole character

of La Nouvelle-Orléans was disappearing and changing quickly. Several factors drew European

immigrants to New Orleans. It was often less expensive to go to New Orleans than to Atlantic ports,

because the large ships carrying Southern agricultural products to Europe returned to New Orleans

with less bulky loads, and offered bargain fares to passengers. New Orleans was also an attractive gateway

to the western interior by steamboats. Other immigrants moved to Louisiana because their

friends and families already lived here. French-speaking people in particular felt more at home in

the Latin cultural environment of southern Louisiana than elsewhere.

New Orleans in 1852. |

By 1820 the city population reached 27,176, surpassing Charleston as the largest city in the South;

by 1860 its population reached 168,675. European immigrants were most responsible for the city’s rapid growth.

In 1860, about 5% of the population of New Orleans was was French, one-tenth was German, one-seventh was Irish .

By 1860 Louisiana was home to the largest Jewish population in the South, numbering about 8,000 residents.

Black refugees from Saint-Domingue brought with them more African and Haitian culture,

such as voodoo, shotgun house architecture, language and dance steps of Mardi Gras Indian rites.

New Orleans was the first place that voodoo appeared in North America.

During the Antebellum, Louisiana also began to attract increasing numbers of Italians, although the majority

of the Italian immigration did not take place until the 1880s and 1890s.

New Orleans harbor in 1852. |

Between 1815 and 1840 the volume of the commercial traffic increased 10-fold and

New Orleans became the second largest American port after New York City.

Between 1815 and 1860 Louisiana plantations cultivated cotton or sugarcane and later rice.

Enormous quantities of cotton, tobacco, grain and meat came down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers by steamboat,

while sugar, coffee, and numerous imported manufactured items were shipped upriver.

Beginning in about 1835, New Orleans became increasingly more dependent on cotton and sugar as export commodities,

as more of the the grain and meat production from the Midwest was transported directly to Northeastern cities

by trains and canals, rather than by ship via New Orleans. The city was having closer and closer ties

with the South, which included the slave trade as an increasingly important form of the city’s commerce.

By 1850 New Orleans was the South's largest slave-trading center. This is reflected in the 1860

population Louisiana, which had grown to 708,002, about half of whom were black slaves.

The rapid growth, and the demographic changes during the 19th century, were reflected in the changing

characted of New Orleans cuisine. In the late 1800s, immigrants from Sicily arrived and encountered established Créole cooking.

Their adaptations formed a new dimension of Créole cuisine. Like the many other earlier influences,

Italian cuisine contributed subtle nuances of taste. Today some of the finest restaurants in the city

are owned by descendants of these Créole-Italians. They serve cuisine that started out as robust Sicilian fare but

developed its current piquant patina through the years of Créole influence.

Original Sicilian cuisine descends from all the cultures which controlled the island over the last

2000 years. It is predominantly Italian-based, it also also has Spanish, Greek and Arab influences.

It is heavily oriented toward seafood, but it also has signs of Arabic influence (apricots, sugar, citrus,

sweet melons, rice, couscous, saffron, raisins, nutmeg, clove, pepper, pine nuts, cinnamon), and Spanish influence

(i.e. maize, turkey, tomatoes from the New World). Typical Sicilian dishes include arancini,

pasta alla norma, pasta con le sarde, caponata, pani ca meusa, couscous al pesce. With the exception of caponata,

one would, however, not find these on the menu in a Créole-Italian restaurant. What happened to Sicilian cuisine

when the Sicilians came to America? Like the French who arrived in la Louisiane in the early 18th century,

the Sicilians found a world with vastly different spices and ingredients. Their cuisine adapted. Much of the cuisine was lost,

such as some of the exotic Arab influences. Saffron was prohibitively expensive in America and fell

away from Sicilian cooking; raisins and pine nuts were omitted; pasta con le sarde fell to the side; tuna was not

as abundant as in Sicily, and certainly was more costly. But many ingredients they were used to from Sicily were abundant,

such as eggplant, peppers, and tomatoes. Those thrived. The most unique feature of the Créole-Italian cuisine

is its tomato sauce, referred to by Neworleanians as "red gravy" or "tomato gravy." Many family recipes exist:

some red gravies are based on a brown roux; some contain eggplant; others contain anchovies, whole boiled eggs, or meat.

Two consistent threads in red gravy are the addition of sugar and the frying of tomato paste.

After the vegetables are sautéed in olive oil, tomato paste is added and fried before the liquids are added.

Créole-Italians incorporate local fish and shellfish in their cooking with delicious results in dishes such as

Shrimp fettuccine. |

crawfish fettuccine, crabmeat in garlic-cream sauce, crawfish and crabmeat cannelloni, spaghetti and oysters

(a twist on the Sicilian recipe that traditionally uses snails), crawfish au gratin, crabmeat-stuffed artichokes,

oysters Francesca, shrimp or crawfish fettucine. Perhaps the most notable Créole-Italian creation is

New Orleans barbecue shrimp. It is a seafood dish, but has nothing to do with barbecuing. The shrimp are

neither grilled nor smoked and there no barbecue sauce. It was created in the mid-1950s at Pascal's Manale Restaurant.

Large whole shrimp are baked in a tremendous amount of butter with black pepper, lemon and Worcestershire sauce.

Nothing like that exists in Italy or anywhere else in the world.

Créole-Italians are also very serious about their pasta. Some Italian-Créole dishes are close cousins of their Italian

ancestors, such as the muffuletta sandwich and shrimp fettucine (although fettucine alfredo is not from

Sicily but from a restaurant in Rome).

Others are built on top of previously evolved Créole recipes such as pasta jambalaya. Other common dishes include

stuffed eggplant and stuffed artichokes.

The waves of Irish and German immigration did not result in there respective fusion dishes being created. There is no

crawfish potato stew or shrimp sauerbraten with dumplings. The Irish and the German cuisines stayed separate.

Our favorite Italian-Créole restaurants include Assunta's, Cafe Giovanni, Pascal's Manale and Sal and Judy's.

There are very few, if any, purely Italian (Northern-Italian or Southern-Italian) restaurants in New Orleans.

When it says "Italian", it usually means Italian-Créole. Top French-Créole restaurants include

Antoine's, Arnaud's, Bayona, Brennan's, Broussard's, Court of Two Sisters, Galatoire's, Tujague's, etc. Typically

Cajun restaurants include Alex Patout's, Cochon, Mike Anderson's or Mulate's.

Sources:

- In Search of La Salle, 2010, KUHT (PBS) and University of Houston System, VHS

- La Louisiane française 1682-1803, http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/celebrations/louisiane/fr

- World Food - New Orleans - Creole, Cajun & Soul For People Who Live To Eat, Drink & Travel,

Pableaux Johnson and Charmaine O'Brien, Lonely Planet, 2000

- Terry Thompson-Anderson, Cajun Creole Cooking, Shearer Publishing, 2003

- Wikipedia

back to Radim and Lisa's Well-Travelled Cookbook | email us

Last updated: November 12, 2010

Photographs from Wikimedia Commons used under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

In the 17th century, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French minister of finance under King Louis XIV,

and Cardinal Richelieu (Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu, Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu),

were the main agents of colonial policy in the Council of the King of France.

Mercantilism inspired the decisions taken to Nouvelle-France, whose development

was entrusted to the government and charter companies formed by investors

for the purpose of trade, exploration and colonization. In 1663 the Conseil

souverain de la Nouvelle-France (Sovereign Council of New France) was created

outside the royal domain to take over from the colonial companies.

Throughout the 17th century, explorers such as Jean Nicolet, Louis Joliet,

Jacques Marquette, Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, and one René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

continued their exploration to the Great Lakes and then south. They discovered Green Bay

west of Lake Michigan, and explored the Missouri, Ohio, Illinois and Mississippi Rivers.

Of particular importance to Louisiana history are the explorations of the Ohio, Illinois

and Mississippi Rivers by de La Salle undertaken in 1669-1670.

In the 17th century, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French minister of finance under King Louis XIV,

and Cardinal Richelieu (Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu, Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu),

were the main agents of colonial policy in the Council of the King of France.

Mercantilism inspired the decisions taken to Nouvelle-France, whose development

was entrusted to the government and charter companies formed by investors

for the purpose of trade, exploration and colonization. In 1663 the Conseil

souverain de la Nouvelle-France (Sovereign Council of New France) was created

outside the royal domain to take over from the colonial companies.

Throughout the 17th century, explorers such as Jean Nicolet, Louis Joliet,

Jacques Marquette, Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, and one René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

continued their exploration to the Great Lakes and then south. They discovered Green Bay

west of Lake Michigan, and explored the Missouri, Ohio, Illinois and Mississippi Rivers.

Of particular importance to Louisiana history are the explorations of the Ohio, Illinois

and Mississippi Rivers by de La Salle undertaken in 1669-1670.

The Natives taught them that the river was navigable and that it flowed into the sea at a place

near the Spanish colonies. As they continued their exploration down the river, the climate gradually

became warmer with alligators inhabiting the waters, the river banks became low and swampy,

the river water brackish. They reached the end of the Mississippi delta on April 9, 1682, near

the present-day port and oil-industry logistics base at Venice, Louisiana. De La Salle

erected a cross and

The Natives taught them that the river was navigable and that it flowed into the sea at a place

near the Spanish colonies. As they continued their exploration down the river, the climate gradually

became warmer with alligators inhabiting the waters, the river banks became low and swampy,

the river water brackish. They reached the end of the Mississippi delta on April 9, 1682, near

the present-day port and oil-industry logistics base at Venice, Louisiana. De La Salle

erected a cross and

La Louisiane joined the other colonies comprising Vice-royauté de Nouvelle-France:

l'Acadie and Canada. The colony of Canada (or New France) was formed in 1534,

and served as the cornerstone of the French colonial empire in North America until 1763.

The colony consisted of three districts: Québec, Montréal and Trois-Rivières.

The governor of Quebec was also the governor-general of all of New France.

The terms "Canada" and "New France" were often used interchangeably. Dependent on the

colony of Canada were the Pays d'en Haute (Upper Country, all of Great Lakes region

and as far west as the French had explored) and Pays des Illinois

(Illinois Country, present-day Mid-western U.S. states).

Canada was ceeded to Britain in 1763 under the Treaty of Paris, following the

French loss of the Seven Years' War.

La Louisiane joined the other colonies comprising Vice-royauté de Nouvelle-France:

l'Acadie and Canada. The colony of Canada (or New France) was formed in 1534,

and served as the cornerstone of the French colonial empire in North America until 1763.

The colony consisted of three districts: Québec, Montréal and Trois-Rivières.

The governor of Quebec was also the governor-general of all of New France.

The terms "Canada" and "New France" were often used interchangeably. Dependent on the

colony of Canada were the Pays d'en Haute (Upper Country, all of Great Lakes region

and as far west as the French had explored) and Pays des Illinois

(Illinois Country, present-day Mid-western U.S. states).

Canada was ceeded to Britain in 1763 under the Treaty of Paris, following the

French loss of the Seven Years' War. When La Louisiane was added to the French colonial empire in North America,

De La Salle returned to France to receive a warm welcome from Louis XIV.

In 1685, he sailed back to America with 4 of the king's ships to continue his colonial ventures

in the Mississippi Valley. However, his second expedition ended in a complete failure.

After losing 3 ships in the Atlantic and in the Gulf of Mexico, his sailors defecting to pirates,

missing the mouth of the Mississippi River, looking for it along the coast all the way to Mexico,

When La Louisiane was added to the French colonial empire in North America,

De La Salle returned to France to receive a warm welcome from Louis XIV.

In 1685, he sailed back to America with 4 of the king's ships to continue his colonial ventures

in the Mississippi Valley. However, his second expedition ended in a complete failure.

After losing 3 ships in the Atlantic and in the Gulf of Mexico, his sailors defecting to pirates,

missing the mouth of the Mississippi River, looking for it along the coast all the way to Mexico,

The Americans were prepared to pay up to $10 million

for New Orleans but were surprised when the vast Louisiana territory was offered for $15 million.

The transaction nevertheless happened and, on a per-acre basis, the United States bought the land for 3 cents per acre, more than doubling its territory overnight.

The Americans were prepared to pay up to $10 million

for New Orleans but were surprised when the vast Louisiana territory was offered for $15 million.

The transaction nevertheless happened and, on a per-acre basis, the United States bought the land for 3 cents per acre, more than doubling its territory overnight.